William Bradbury

Family Overview

- Mother: Elizabeth Hardwick (1774-1820)

- Father: John Bradbury (1776-1834)

- Wife: Sarah Price (1803-1898)

- Children: Letitia Jane Bradbury (1827-1839); Henry Riley Bradbury (1829-1860); William Hardwick Bradbury (1832-1892); Walter Bradbury (1840-1891); Edith Bradbury (1842-1910)

Early Years

On Saturday 13 April 1799, [1] in the beautiful market town of Bakewell, Derbyshire, England, printer and publisher William Bradbury was born to parents John Bradbury (1776-1834) and Elizabeth nee Hardwick (1774-1820). William was their first child; his twenty-three year old father John worked as a shoemaker and he and Elizabeth had married at the parish church of All Saints, Bakewell the previous summer. [2] William was baptised at this same church the day after his birth. [3] John and Elizabeth came from families with a long established history in Bakewell. John was the eldest of eleven sons and one daughter born to Ralph Bradbury (1754-1833) and his wife Hannah nee Redfern (1755-1833). Nine of these children survived to adulthood. Ralph was clearly an educated man who worked as the parish clerk. He was also the schoolmaster at Mary Hague's school in Bakewell, founded in 1715 from a legacy left by local woman Mary Hague, who died in March 1715. Her legacy had originally been intended for the education of seven poor girls from the town, however by the time of Ralph's appointment as schoolmaster the school was educating both girls and boys.

There appears to have been a long tradition of shoemaking amongst the Bradbury family, stretching back to at least the 1740s when William's great-grandfather John Bradbury (c.1720-1768) worked in Bakewell as a shoemaker. [4] All but one of Ralph and Hannah's surviving sons worked as craftsmen. William's father John and his brothers Joseph (1783-1866), Thomas (1791-1869), Benjamin (1793-1859) and Samuel (1797-1848) all worked as shoemakers; their brother George (1790-1834) worked as a hatter and their brother James (1787-1861) worked as a lace maker in Sneinton, Nottingham. By the year 1829 Bakewell had thirty-seven people working as shoemakers serving a local population of around one-thousand nine-hundred people. [5]

William was soon joined in the family by siblings Charles (b.1801); [6] Mary (1803-1850) [6]; Orlando (1805-1872) [7]; and Philip Alexander (1806-1856). [7] Unfortunately I have been unable to establish any unequivocal facts regarding the life of William's brother Charles, and it may be that he died young. Philip was baptised at the parish church in Bakewell on 21 September 1806. At some point after that date and before 22 July 1811, [8] when John Bradbury witnessed a marriage at the parish church of St Mary Magdalene, Lincoln, John, Elizabeth and the children moved almost sixty miles eastwards from Bakewell to live and work in the cathedral city of Lincoln, Lincolnshire. They were joined there by John's unmarried younger brother George.

The Church of St Mary Magdalene, Lincoln, where William Bradbury's family worshipped. Photograph by David Wright via Wikimedia Commons License CC BY-SA 2.0

John, Elizabeth and the children took a house in the Bailgate area of the city, an historic area which runs southwards from a Roman gateway known as Newport Arch, through to Castle Hill where the cathedral and castle are located. They were worshippers at the church of St Mary Magdalene which sits almost immediately against the cathedral. William's uncle George, a hatter, took a property about a quarter of a mile away on the Strait. This narrow stretch of cobbled street sits at the bottom of Steep Hill, the aptly named hill that leads directly to Castle Hill and the cathedral. Interestingly it would seem that when the family arrived in Lincoln, William's father John left the craft of shoemaking behind and became a Yeoman farmer.

Early nineteenth century Lincoln was very much a city divided into two parts: above hill and below hill. Above hill Lincoln was predominantly the home of the wealthier members of society, the gentry and the clergy. When William and his family arrived in Lincoln, the city primarily consisted of one main street which stretched northwards for approximately two miles up to Steep Hill and the cathedral and Castle Hill. In 1810 above hill Lincoln was rather brutally described as "quite offensive to the eye, from the confusion and jumble it presents: indeed, the most picturesque objects are only so at a distance; farther removed they lose their force; brought nearer, they display too many abrupt lines, and too much harshness of contour to be pleasing." [9]

Choral singing played an extensive role in the lives of several members of William's family; his father John, his paternal uncles George and Benjamin, his brother Orlando and cousin George Frederick (1816-1850), were all choristers. John and his son Orlando were bass singers and George was a tenor. I wonder if it was this love of, and talent for, singing that was the catalyst for the family's move to Lincoln in the early 1800s. In 1808 the cathedral choir were looking for a "Singing Man with a Tenor Voice" [10] and it may have been this advertisement that prompted George's move to Lincoln. Both John and George and their sons Orlando and George Frederick became choristers in the choir of Lincoln cathedral, with John and George retaining their positions until their deaths in 1834.

In the summer of 1813 fourteen year old William Bradbury was enrolled in a seven year apprenticeship with the richly experienced Lincoln printer John Drury (1757-1815). John Drury had worked in the printing industry in Lincoln since his own apprenticeship in 1771 at the age of fourteen. He worked from premises above a late fifteenth century stone building known as the Stonebow, which still today forms a striking gateway over Lincoln's main High Street. The wider Drury family were steeped in the printing industry, with businesses in Lincolnshire, Derbyshire, Staffordshire and London. John Drury's nephew was the publisher John Taylor (1781-1864) who founded the London publishing house of Taylor and Hessey. Taylor and Hessey acted as publishers for some of the greatest writers and poets of their time, people such as John Keats, William Hazlitt, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Lamb and John Clare. In 1818 John Drury's youngest son Edward Bell Drury (1797-1843) became the proprietor of the New Public Library in Stamford, Lincolnshire, which was both a bookshop and lending library. He formed a friendship with the then unknown and unpublished poet John Clare (1793-1864) who lived in the nearby village of Helpston. Recognising something of worth in Clare's poetry Edward Bell Drury liaised with his cousin John Taylor in London. On 15 January 1820 John Clare's first volume of poetry was published jointly by Taylor and Hessey, London and E Drury Stamford under the title "Poems, Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery".

Sadly John Drury died at the age of fifty-seven two years into William Bradbury's apprenticeship. The business was carried on by John's wife Jane (1761-1832) and two of their sons, John Wold (1789-1850) and James (1793-1851) under the name of Drury and Sons. William Bradbury continued to learn and develop his craft under their guidance.

On Thursday 15 September 1814 William's uncle George married local woman Anne Allen (1790-1827) at the parish church of St Peter in Eastgate, Lincoln, and their first child, a daughter Charlotte (1815-1819) was baptised the following summer. Charlotte was soon joined by a brother, George Frederick (1816-1850) the following year.

In December 1819, six years into his apprenticeship with the Drury family, William was joined at the printing office by his fourteen year old brother Orlando, who was apprenticed to John Drury's son John Wold Drury. William's youngest brother, Philip Alexander, did not follow his older brothers into the printing industry. Instead in May 1821 he was apprenticed to Thomas Norton (c. 1769-1852), one of the city's linen and woollen drapers. Thomas Norton, who was the city's mayor on several occasions, ran a successful drapery business with his nephew John Norton as Thomas Norton and Co, and subsequently as Thomas Norton and Nephew, from premises on Lincoln's High Street. In 1832 the business moved to impressive sounding new premises, described as being "laid out with considerable taste, and lighted by three dome lights, in one of which some allegorical figures are placed with considerable effect. The coup d'oeil is most effective and imposing." [11] It is somewhat harder to write about the life of William's only sister Mary at this time. It is most probable that she was at home helping her mother with the running of the household, for their home life had in fact taken a very distressing turn. William's mother Elizabeth had become extremely unwell. There is no record of the exact nature of her illness, but she apparently bore a long period of severe ill health with "exemplary fortitude" before dying on Wednesday 26 April 1820 at the age of forty-five. [12].

Young Adulthood

Castle Hill Lincoln site of William Bradbury's first printing office in 1821. Author's own photograph.

William completed his apprenticeship under the supervision of Jane and John Wold Drury and at a common council at the Guildhall, Lincoln on Thursday 21 June 1821, he was made a Freeman of the City of Lincoln. Years later his business partner Frederick Mullett Evans would say to friends that William

"has worked his way up from being a printers boy, has printed at case, and his great taste has much improved the style of printing." [13]

On Friday 30 November 1821, a small notice appeared inside the Stamford Mercury newspaper announcing to the citizens of Lincoln that a new printing office had opened in Castle Hill. This was William Bradbury's first business venture. A keen, determined and ambitious young man, he had taken the first steps on the path that would see him remembered as "the keenest man of business that ever trod the flags of Fleet Street". [14] William appears to have operated this first printing office alone.

However, less than three months after opening this office, William Bradbury moved his business down into the commercial heart of the city, taking a property in the area known as the Cornhill. This new printing office was situated in a building adjoining a hosiery and lace manufactory, owned by a gentleman called Richard Moulding (c.1792-1842). [15] Writing twelve years previously Adam Stark had said of the Cornhill:

"... nearly opposite to St Benedict's, is a small square, used as a corn market, which from the celebrity of this place as a mart for grain, appears evidently too confined.- Lincoln, indeed, with all its advantages, does not seem to enjoy that of a good general marketplace; for the street from the cornhill to the butter market, is, on a market day, literally choaked up with stalls and standings, to the great annoyance of passengers, and inconvenience of the neighbouring housekeepers : it is, indeed, a nuisance which calls loudly for removal, and a grievance which it behoves the magistrates seriously and speedily to redress." [16]

There was at least one other printing office in the Cornhill area established and run by a gentleman named John Smith (b.a.1776-1846). He had opened his printing firm in a shop opposite the Cornhill in June 1799. In January 1823 printer John Wold Drury also moved close by when he took over premises on the High Street facing the Cornhill. It is highly likely that William Bradbury's office would have been constructed mainly from wood like so many buildings in the city were, with all the associated risks for fire. Just three months after Bradbury had moved to his new office a fire had broken out at midnight in a firm of linen drapers in the Cornhill. Fortunately the fire was quickly discovered and the flames extinguished, albeit with some difficulty, by neighbours before it could spread to adjacent buildings. It had most probably been caused by a spark from a lighted candle. [17]

A year after William started out in business he was joined at the printing office by his future brother-in-law William Dent (1792-1858), a printer who had been raised by his maternal grandparents ninety-seven miles from Lincoln in the town of Bedford, Bedfordshire. Quite what brought William Dent to the city of Lincoln, and how he and William Bradbury met, remains a mystery. However on Friday 15 November 1822 a notice appeared in the Stamford Mercury which read:

"W BRADBURY, Printer, Bookseller, Book-binder, and Stationer, Cornhill, LINCOLN, for the very liberal patronage which has been extended to him since his commencement in business, desires to tender to his friends and the public his sincere and grateful thanks; and he respectfully informs them, he has entered into Partnership with Mr. W. DENT, humbly soliciting a continuance of that kindness which has hitherto attended his endeavours, assuring those friends who may honor them with their patronage, that their united efforts will ever be exerted to give satisfaction.- Any orders, however small will be gratefully received, and executed on the most liberal terms." [18]

Bradbury and Dent settled into their business partnership, offering the people of Lincoln their services as printers, booksellers, bookbinders and stationers. As the business thrived a close friendship developed between William Dent and Bradbury's sister Mary, and the two soon became romantically attached.

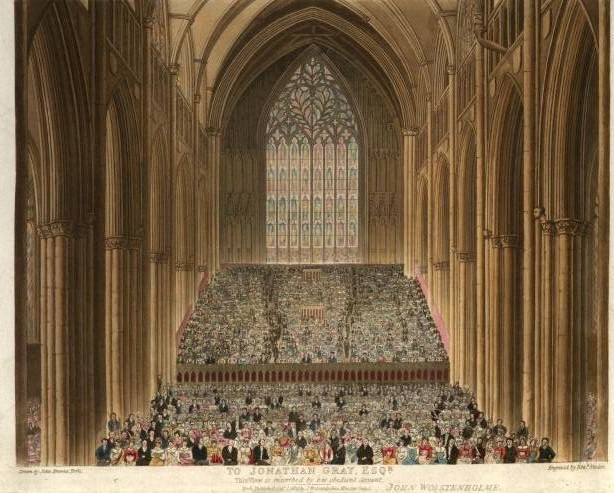

Engraving by Edward Francis Finden of the York Music Festival held in York Minster in September 1823

The choral talent of William's father John and uncle George led to them being part of a wonderful experience over the course of four days in September 1823. They both had the honour of being chosen to perform in a magnificent musical festival held in York Minster, approximately seventy miles north of Lincoln. The spectacular event was held to raise funds for the York County Hospital and the infirmaries at Leeds, Sheffield and Hull. The streets of York echoed with the clatter of horses and carriages as approximately three to four-thousand people gathered in the minster each day to listen to the vocalists and an orchestra made up of almost five-hundred performers. The grand proceedings were opened by the Archbishop of York. On the third day of the festival, Thursday 25 September, George had the distinction of being one of only eight tenors selected to be in the semichorus. [19] Lavish balls were held on the Wednesday and Friday evenings in the Assembly Rooms, with dancing to the celebrated quadrille band of Messrs Michau, Musard and Collinet. The Assembly Rooms had apparently never before been filled with "so brilliant an assemblage of rank, fashion and beauty, as was now presented to the delighted eye. The dresses of the ladies were many of them exceedingly magnificent, and the display of diamonds was splendid beyond any former precedent within those walls." [20] The festival was a huge success, raising more than £15,000 and must have been an absolutely exhilarating few days for the Bradburys.

The Move to London

The autumn of 1824 brought huge changes to the lives of William Bradbury, his sister Mary and William Dent. The printing office had proved to be a successful venture, but Bradbury in particular appears to have been a driven, focussed man with great ambition. Early nineteenth century Lincoln just wasn't large enough to offer William the capacity for growth that he envisioned, and so a decision was made to leave Lincoln and take the business to London. William Dent had actually been born in London, and his older brother Edward John Dent (1790-1853) was still resident there. He went on to become a celebrated watch and clockmaker and in 1852 won the commission to make the clock for the Palace of Westminster clock tower known as 'Big Ben'. William Bradbury and William Dent left Lincoln for London around the September of 1824; the Lincoln printing office in the Cornhill was taken over by printer, bookbinder, bookseller and stationer John Hall (1792-1872).[21] Once in London Bradbury and Dent headed straight to the heart of the London printing industry, opening their first London office on the third floor of a shared building at 76 Fleet Street.[22]

On Saturday 4 June 1825, a few months after their arrival in London, Mary Bradbury and William Dent were married at St Bride's Church on Fleet Street. The church describes itself as the "spiritual home of the media" and has been associated with the printing industry since the sixteenth century when Wynkyn de Worde first set up his printing press on Fleet Street. Mary and William were both described in the marriage register as being resident in the parish, and their brothers William Bradbury and Edward John Dent witnessed the marriage.[23] William and Mary took a house in the parish of St James, Clerkenwell, and Mary gave birth to their first child, a boy named after William's brother Edward John, on Saturday 4 March 1826.

Bradbury and Dent had, unwittingly picked a particularly difficult time economically in which to try to expand and grow their business. In April 1825 the London stock market crashed, leading to the closure of some high-profile London banks, and by the end of the year a financial panic had gripped the country. However, despite the economic crisis, Bradbury and Dent thankfully managed to find sufficient work to maintain their fledgling business.

The Lincoln Bradburys seem to have kept in close contact with the extended family in Bakewell. Living in Bakewell at this time was a young woman by the name of Sarah Price (1803-1898). Sarah's parents John Price (1775-1855) and Jane Cawdron Price (nee Riley) (1782-1859) had both been born elsewhere in the country, but had married at All Saints church Bakewell in November 1802. Sarah's maternal grandfather Eli Edward Riley (c.1760-1800) had worked as a brandy merchant in London in the 1780s, before falling on hard times and declaring bankruptcy in 1788.[24] Following a spell in the Fleet Prison he appears to have moved to the town of Bakewell, where he died in the summer of 1800. It may be that the Price and Bradbury families knew each other well; on the 1841 census of England and Wales, Sarah's parents were living next door to John and George Bradbury's cousin James Bradbury (1785-1855) and his daughter Mary.[25] We do not know exactly how they met, but William Bradbury and Sarah Price fell in love with each other and married on Thursday 6 July 1826 at the parish church of All Saints, Bakewell, the church in which they had both been baptised. Sarah is listed on the marriage register as being resident in the parish, and William is recorded as being resident in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, London, which is less than half a mile from Fleet Street.[26] Following their marriage William and Sarah returned to London and set up home together; William continued to work in partnership with his brother-in-law William Dent. Sarah quickly became pregnant and, no doubt to their great delight, a daughter Letitia Jane Bradbury was born the following summer. She was baptised, like her parents, at the parish church in Bakewell on 17 August 1827.

Back in Lincoln, William's brother Orlando became a Freeman of the City in November 1826 upon completion of his apprenticeship as a printer with John Wold Drury. Orlando's great passion, however, appears to have been music. Like his father and uncle he was a chorister at the cathedral, studying as a pupil of choir master Benjamin Whall (c.1780-1855). At the end of July 1826 Orlando was appointed as the organist at St Peter at Arches church,[27] a church which stood just to the north of the Stonebow in Lincoln until its demolition in 1932. Like his older brother, however, Orlando seems to have had ambitions that necessitated a move to London. In the winter of 1827, at the age of twenty-two, he was appointed deputy for John Sale (1758-1827) at St Paul's Cathedral and Westminster Abbey.[28] Mr Sale, who died on 11 November 1827, was a distinguished bass singer and a favourite of Kings George III and George VI. He was Senior Gentleman of the Chapel Royal and had been vicar choral St Paul's and lay vicar of Westminster Abbey. He was buried on 19 November 1827 in St Paul's Cathedral.[29]

Two months after little Letitia Jane's baptism tragedy befell William's uncle George in Lincoln with the death of his wife Anne on Wednesday 24 October at the age of thirty-seven.[30] George was left with four young children aged between three and eleven years old. George and Anne's eldest daughter Charlotte had died in 1819 aged just four, and tragically a mere nine months after Anne's death, their daughter Elizabeth died at the age of five. Brothers John and George were now both widowed; they still sang together in the cathedral choir and lived within half a mile of each other.

There was much happier news for the wider family as John became a grandfather again when William Dent and Mary had a little boy, William Henry, in May 1828, followed by William and Sarah having a son, Henry Riley Bradbury, on Sunday 20 September 1829. William's brother Philip Alexander became a Freeman of the City of Lincoln in May 1828 on completion of his apprenticeship with draper Thomas Norton. Firmly established in his new life in London, William's brother Orlando married a young woman named Clarissa Barclay on 24 October 1830 at the Grade 1 listed church of St George's, Bloomsbury.

William and Sarah settled into family life in a newly built house in Wingrove Place, (now Corporation Row) Clerkenwell, approximately one mile northwards from William's business interests in and around Fleet Street. In the late 1820s Bradbury and Dent were undertaking printing work for the publishing house of Hurst, Chance and Co, who operated from premises at 65 St Paul's Churchyard. A young man by the name of Frederick Mullett Evans was working for the publishing firm in 1828, and it is possible that William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans became acquainted with one another at this time. The two men must have recognised something in each other that led them to believe that their working lives lay together. It would seem that their personalities balanced each other; Frederick appears to have been an extroverted, sociable young man in contrast to William's more introverted, more direct nature. On 31 December 1829 William Bradbury and William Dent officially dissolved their business partnership, although they would obviously remain a part of each others lives through their familial connection. A short time later William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans set up their first printing office together at 1 Bouverie Street, Whitefriars, London.

The Middle Years

Once again William's business had to weather an economic storm; the country was experiencing a profound financial depression which unfortunately saw over six-hundred printers lose their businesses by the autumn of 1831. Amidst this financial and political turmoil there was however a moment of celebration for the nation with the coronation of King William IV (1765-1837) and Queen Adelaide on 8 September 1831. Streets and businesses were lavishly and richly decorated, and Bradbury and Evans embraced the celebrations festooning their office windows with sumptuous garlands.[31] Bradbury and Evans' new printing office seems to have not only survived the economic crisis but actually to have thrived primarily due to the relationships they were establishing and their keen business sense. Between one and two years after opening this first printing office at number 1 Bouverie Street, Bradbury and Evans moved their business further along that same street, opening an office at number 22. Around this same time William, Sarah and the children moved home, leaving the house in Wingrove Place, Clerkenwell and taking up residence at 22 Bouverie Street itself, placing them directly at the heart of the business. On Monday 3 December 1832 Sarah gave birth to their third child, a son, William Hardwick Bradbury; most distressingly that same month there was further tragedy for William's uncle George in Lincoln as his young daughter Sara died aged eight years old. George had suffered the loss of two daughters and his wife over the course of five years.

Bradbury and Evans' business continued to flourish and in 1833 the partners decided to take over some vacant premises on adjacent Lombard Street (now Lombard Lane). For more than thirty years these buildings had been occupied by the well respected printer Thomas Davison, before his death at the end of 1830. Under Bradbury and Evans' proprietorship these new Lombard Street premises had six presses which roared along continuously for twelve hours each day, and also a brand new stereotype foundry. In February 1834 Bradbury and Evans began printing gardener and architect Joseph Paxton's new monthly magazine The Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants for London publishers Orr and Smith. This initial contact led to the formation of a deep, life-long friendship between Joseph Paxton and William Bradbury.

Most regrettably there was dreadful news from Lincoln as William's father John died at the beginning of February 1834.[32] He was fifty-eight years old and was buried at the church of St Mary Magdalene, Lincoln on 6 February 1834. At the time of his death John was living on the Strait which is the small stretch of cobbled street at the bottom of Steep Hill. This is the same small area that George lived in, and I wonder if the two brothers were living together. Both men unfortunately appear to have been seriously unwell in 1834; on 19 October George died at the age of forty-five following a long period of ill health.[33] As he had spent all of his working life labouring as a hat maker I wonder if his death was connected with the handling of mercury used in their manufacture. John's death in February 1834 was particularly poignant as his daughter Mary was pregnant with her third child. On Thursday 7 August 1834 at her home, 3 Gray's Terrace, Southwark, London, Mary gave birth to another little boy whom she named Orlando Philip Dent after two of her brothers. [34]

William's wife Sarah had a brother named John Price (1808-1858). Like his sister John was born in Bakewell, Derbyshire and made the move from there to live and work in London. It would seem that whilst in London he met and fell in love with a young lady by the name of Ann Nelson (1816-1888), the daughter of Robert Nelson (1791-1850) hotel keeper and proprietor of the Belle Sauvage Coaching Inn on Ludgate Hill, London. On Saturday 6 February 1836 John Price and Ann Nelson married at the church of St Bride, Fleet Street. [35] Ann's family were well-known in London as coach operators with an office at 52 Piccadilly. The coaching business was headed up by her paternal grandmother and namesake Ann Nelson (1770-1852), a strong-minded businesswoman who ran the Bull Inn, Aldgate. John and Ann Price took a house on Fleet Street where John initially worked as a woollen draper. Ann was probably in the early stages of pregnancy when they married and she gave birth to a son Harry Nelson Price (1836-1901) on Friday 11 November 1836. [36]

In the April of 1836 there was another terrible account from Lincoln with the death by drowning of William's sixteen year old cousin Charlotte, the youngest surviving child of George. It would appear that Charlotte had been out walking along the banks of the Fossdyke canal at around three o'clock in the afternoon on Thursday 7 April. She had been employed as a live-in servant and had unfortunately been dismissed earlier that day due to a dispute with her employer, leaving her homeless. She had met an acquaintance of hers a little earlier in the day and had spoken to him about how miserable she was feeling. She was seen walking by the canal by a man with a horse drawn carriage. Shortly after passing her he heard a scream. He and another passer-by immediately stopped their horses and ran down to the water's edge where they saw Charlotte in the canal struggling and fighting for her life. However neither gentleman were able to swim and they were too afraid to enter the water themselves. As they stood and watched Charlotte from the riverbank she slipped under the water, weighed down by her sodden and cumbersome clothing. Making the assumption that she was now beyond help, they left. Approximately fifteen minutes later they passed a horse rider and informed him of the tragedy; he rode into the city to try to establish which particular parish that part of the Fossdyke was in, in order to notify the correct authorities. After some time the parish constable was located and informed and poor Charlotte's body was eventually retrieved from the river. The inquest verdict was "Found Drowned". [37]

In September 1836 there was some wonderful news for the family with the appointment, by the Bishop of London, of Orlando to serve in the household choir of the royal family as one of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal. [38] In the spring of 1843 he was appointed Lay-Clerk of Westminster Abbey by the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, succeeding chorister and musician Thomas Vaughan (1781-1843) who had died in January 1843. [39]

Bradbury and Evans' business continued to prosper. They had established a reputation for speed, reliability and excellence and by 1836 they were undertaking work for the publishers Chapman and Hall. Publisher William Hall visited a young writer to ask if he would be willing to compose some text to accompany some comic illustrations created by caricaturist Robert Seymour (1798-1836). This young writer, who agreed to William Hall's proposal, was Charles Dickens (1812-1870). Bradbury and Evans were chosen by Chapman and Hall as the printers for this new work, and on 31 March 1836 the first part of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club was published in its distinctive green wrappers. Thus began a working relationship between William Bradbury, Frederick Mullett Evans and Charles Dickens that would see Bradbury and Evans as Dickens' publishers from 1844, an association that would last until an acrimonious split with Dickens in 1858. By the spring of 1838 Bradbury and Evans had increased their workforce to more than one-hundred and forty people. [40] Three years later at the end of 1841 Bradbury and Evans had become the sole printers of the weekly satirical magazine Punch, and by the end of the following year had been persuaded by the first editor Mark Lemon (1809-1870) to become the proprietors. Bradbury's brother-in-law John Price had taken over proprietorship of the Belle Sauvage Coaching Inn from his father-in-law Robert Nelson. In those early Punch days a tradition evolved that was to last for more than one-hundred years. The editor, writers and illustrators of the magazine would meet weekly in a congenial atmosphere over food and drink and would debate, argue and joke over subjects such as politics, social issues of the day and business. Under Bradbury and Evans' proprietorship these weekly meetings took on a more focused character where, following a 6.30pm dinner, ideas for the weekly full-page illustration were vigorously discussed and a subject eventually decided upon. William's good friend Joseph Paxton was the only non staff member to be permitted to dine at the dinners. The first of these Punch meetings was held at the Belle Sauvage Inn.

However, as his business continued to prosper William and his wife Sarah suffered the most terrible personal tragedy. On Friday 1 March 1839 their daughter Letitia Jane died at home at the age of eleven.[41] She had been suffering with heart and lung problems. [42] William and Sarah must have been absolutely devastated. The following day a distraught William penned a note to Charles Dickens informing him of Letitia's death. Dickens replied from his Doughty Street home with a long note of condolence in which he expressed his "heartfelt pain and sorrow". William and Sarah had taken a house at 1 Clarence Terrace, Albion Road, Stoke Newington. On Saturday 9 March 1839 young Letitia Jane was buried in the church yard of the beautiful old church of St Mary's, Stoke Newington, a very short distance from her home. Almost a year to the day from Letitia's death Sarah gave birth to her fourth child, a little boy whom they named Walter. [43] Two years later on Tuesday 5 April 1842 Sarah gave birth to her fifth and final child, a daughter named Edith. [44] The family had also moved a short distance, taking a house at 6 York Place, Albion Road, Stoke Newington. Sarah had help with the management of the household from two young live-in servants, twenty-three year old Amelia Turner and twenty year old Susannah Davis. Amelia Turner, who never married, remained with the Bradbury family for over thirty years, becoming a nursemaid in Edith's household following Edith's marriage in 1864.

Later Years

As the business prospered William, Sarah and the family moved to 13 Upper Woburn Place, London, an elegant Georgian house situated close to Tavistock Square. This was to remain William's home until his death. Distressingly there were two more tragic events for the family to come to terms with. William's young nephew Orlando Dent died at his home on 10 September 1850 from pulmonary tuberculosis aged sixteen years old. An announcement in The Times newspaper the following day read:

"On the 10th inst., of consumption, aged 16, Orlando Philip Dent, the beloved son of Mr. William Dent, of Calthorpe-street, and nephew of Mr. Edward J. Dent, 82, Strand."

He was buried at Highgate Cemetery four days after his death. Shockingly just a month after Orlando's death, on Friday 11 October 1850 William's sister Mary died. She too died at home aged forty-seven; she had been suffering from bronchitis for the previous eighteen months. Her death was not announced in The Times newspaper, however an announcement in the London Evening Standard on 14 October 1850 simply read:

"On the 11th inst., Mary Dent, the wife of William Dent, formerly of Bedford."

She was buried in Highgate Cemetery in the same grave as her son just one month and one day after his interment.

Five years later there was more melancholy news with the death in Bakewell of Sarah's father. This was swiftly followed the next year by the untimely death of William's youngest brother Philip Alexander on 14 December 1856. [45] Philip had never married and following his apprenticeship as a draper he had found employment as a commercial traveller. He lived with their brother Orlando and his wife Clarissa for a while but at the time of his death was living on Cornwall Road in Hammersmith, London. It would seem that his death was sudden and unexpected, the cause being given as apoplexy. It may have been that he suffered a stroke or aortic aneurysm. He was fifty years old.

Over the years William Bradbury's and Charles Dickens' families had formed a warm friendship. Dickens affectionately referred to William as Beau B, and the two families would often dine and socialise together. In the late spring of 1858 Dickens separated from his wife Catherine. Gossip was rife in London concerning Dickens having an extra-marital relationship with either his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth or an actress, Ellen Ternan. In an attempt to quell the public gossip Dickens issued a statement regarding the separation, which was published in The Times newspaper on 7 June and in Household Words on 12 June 1858. However, unbeknownst to either Bradbury or Evans, Dickens had expected that this statement would also be published in the following week's Punch. When he realised that the statement had not been printed in Punch Dickens was furious, taking the non-appearance as a personal insult. He resolved to sever all business and personal ties with them as a result. When Bradbury and Evans were informed of this reaction they were in disbelief; as they later wrote "it did not occur to Bradbury and Evans to exceed their legitimate functions as proprietors and publishers, and to require the insertion of statements on a domestic and painful subject in the inappropriate columns of a comic miscellany." [46] Bradbury and Evans had acted as Dickens' publishers since 1844. However following this dispute Dickens ceased all contact with them and returned to his former publishers Chapman and Hall. Production stopped on their joint collaboration Household Words. Dickens established a new publication All the Year Round and Bradbury and Evans founded an illustrated weekly magazine of their own which they called Once a Week. The editor of this new publication was the journalist Samuel Lucas (1811-1865), and many of Bradbury and Evans' friends and colleagues from Punch also joined with them on the staff of Once a Week, including the illustrator John Leech and writers Mark Lemon and Shirley Brooks.

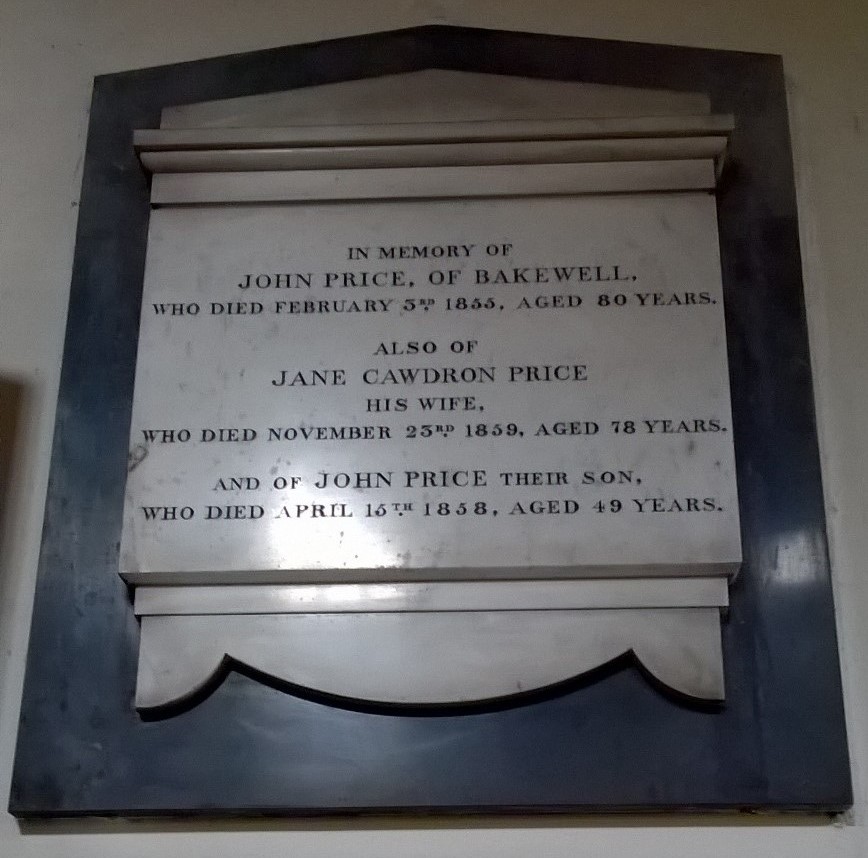

Memorial to Sarah Bradbury's parents and brother high on the wall inside All Saints Church, Bakewell, Derbyshire. Author's own photograph.

William and Sarah had recently suffered the loss of Sarah's brother John Price, who died on 15 April 1858 in Bakewell from bronchitis at the age of forty nine. [47] John had had severe financial hardships in London, which culminated in bankruptcy and him spending nine months in Whitecross Street debtors prison in the late 1840s. He had sunk into this parlous financial state whilst farming in the Plaistow area of east London and running the Belle Sauvage Inn on Ludgate Hill; Dolly's Chop House (near St Paul's Cathedral), Queen's Head Passage, Newgate Street, London; and the Portland Hotel on Great Portland Street, London. The petitioner in the bankruptcy case had been John's brother-in-law James Crighton Nelson (c.1820-1885). [48] John and his wife Ann had at least nine children; the strain upon the family during John's incarceration must have been enormous. At some point following his release from prison John and Ann moved back to his birth town of Bakewell, where he, Ann and the children rented a house on Matlock Street. [49] Very sadly John's death was followed by the death of his and Sarah's mother Jane, who died in the November of 1859. [50] She was buried with her husband and son at the church of All Saints Bakewell on 27 November 1859. A memorial to Jane, her husband John and their son John can be found high on the wall inside the church.

At the end of the particularly wet summer of 1860 William and Sarah were looking forward to celebrating the forthcoming marriage of son William Hardwick to Laura Agnew (1834-1920), daughter of Manchester art dealer Thomas Agnew (1794-1871) and his wife Jane. William and Sarah's three sons were growing into fine young men; oldest son Henry Riley, had, like his brother William Hardwick, followed his father into the printing industry. In the early 1850s he spent some months studying at the Staatsdruckerei, the imperial printing office in Vienna, whose director at that time was printer and illustrator Alois Auer (1813-1869). [51] Whilst there Henry learned of Auer's nature printing technique. This was an ingenious technique which involved the use of a natural object such as a plant leaf. The item would be placed between two metal plates and an enormous pressure exerted upon it. This force impressed an exact copy of the object into the metal plate. Reproductions of this metal plate would then be made by electrotyping, from which finely detailed prints of the original item could then be produced. This approach lent itself particularly well to the printing of plants such as ferns. Upon his return to England Henry made some enhancements to Auer's technique which he then patented. On 31 March 1855 Henry published, in large folio, part one of seventeen monthly parts of The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland, using his nature printing technique. Botanist Thomas Moore (1821-1887) was the author and botanist and gardener John Lindley (1799-1865) was the editor. The monthly parts were published from Bradbury and Evans' premises at 11 Bouverie Street, and were priced at 6 shillings each. [52] Most unfortunately a bitter dispute arose between Henry and Alois Auer, as Auer felt that Bradbury had not acknowledged the fact that he had first come across the nature printing technique in Vienna and had, in fact, given the impression that he had invented the process himself. Regrettably the controversy became very acrimonious with Auer insulting Bradbury's character in print. Notwithstanding this, the enterprising Henry established his own business in partnership with a young man named Robert Wilmot Wilkinson (1827-1910), the son of Henry Wilkinson a copper plate printer and his wife Ann. Together the two men traded as Bradbury and Wilkinson from premises in Fetter Lane, a five minute walk northwards from Bouverie Street. The company's specialism was the printing of banknotes.

Early in the evening of Saturday 1 September 1860, Henry Bradbury arrived at the magnificent Cremorne Gardens, situated alongside the River Thames in Chelsea. Very popular with Londoners these pleasure gardens had sweeping grounds filled with all manner of delights and entertainments such as elegant dining areas, dancing, an orchestra, and glittering firework displays. However, by that September the gardens had also acquired a very dubious reputation of an evening; local residents were extremely vocal in their exasperation at the activities that took place there late at night. At a very vocal meeting vestryman Mr Hulse reported on the residents' behalf:

"Harlots dashed down their streets on their way to the gardens, in cabs from town, decked out in jewels and puffing their cigars, all evenings of the week, early and late. The result of this was that large numbers of private houses erected in the neighbourhood, instead of being occupied by respectable families, were turned into brothels." [53]

Over the previous two years concern had been building amongst Henry's friends regarding his behaviour. He had been so uncharacteristically intolerant at times that there was apparently no discussing or reasoning with him. It was rumoured that he had an alcohol problem, Alois Auer had referred to him as a "dishonest drunk". That particular weekend Henry was very obviously troubled; it was reported that he had spent the previous two days drinking heavily in numerous public houses. Clearly agitated, Henry arrived at Cremorne Gardens and started to act rather strangely. He seemed unsettled with rapid changes of mood. He approached one of the waiters, a Mr Irwin, and asked to be shown to a quiet seat. Mr Irwin duly took him to a seat under a bower, where Henry asked for a glass of gin and water. Mr Irwin suggested instead that Henry have a bottle of soda water, and Henry agreed. After emptying the water into a glass Mr Irwin took the bottle away. He had gone no more than a few steps from Henry before he heard an almighty thud. Henry was lying on the ground. Mr Irwin and one of the other waiters tried to lift him, but he was too heavy. The local Constable was immediately called. He concluded that Henry had ingested poison. A doctor, Mr Hopewell from nearby Beaufort Street quickly arrived, but it was too late. Henry was dead. [54] On the table where he had been seated was what remained of his glass of soda water into which Henry had poured prussic acid, an extremely poisonous, colourless liquid. Alongside the glass was a bottle which reportedly contained enough prussic acid "to destroy at least 20 lives." [55] At an inquest held in the evening of Monday 3 September 1860 at the World's End Tavern, on King's Road, Chelsea, the inquest jury returned a verdict of "temporary insanity". Henry was buried in Highgate Cemetery, London on Wednesday 5 September 1860. He was thirty years old. William and Sarah must have been completely heartbroken.

On Tuesday 4 September Charles Dickens wrote to his close friend the journalist William Henry Wills (1810-1880) and mentioned Henry's death in the letter. Clearly rumour and speculation were rife regarding the circumstances of Henry's demise. Apparently Frederick Chapman of publishers Chapman and Hall had written to Dickens the previous evening informing Dickens that Henry's death had occurred at the family home. Dickens went on to say to Wills that someone else had told him that the death had happened in Cremorne Gardens, but that he did not know which account was correct. Dickens gave a bleak description of walking past the Bradbury home at Upper Woburn Place that morning stating that the house appeared "grim and dry, with all the blinds down, brooding in a hot, dusty, tearless, frozen kind of way, at the unsympathetic street." [56]

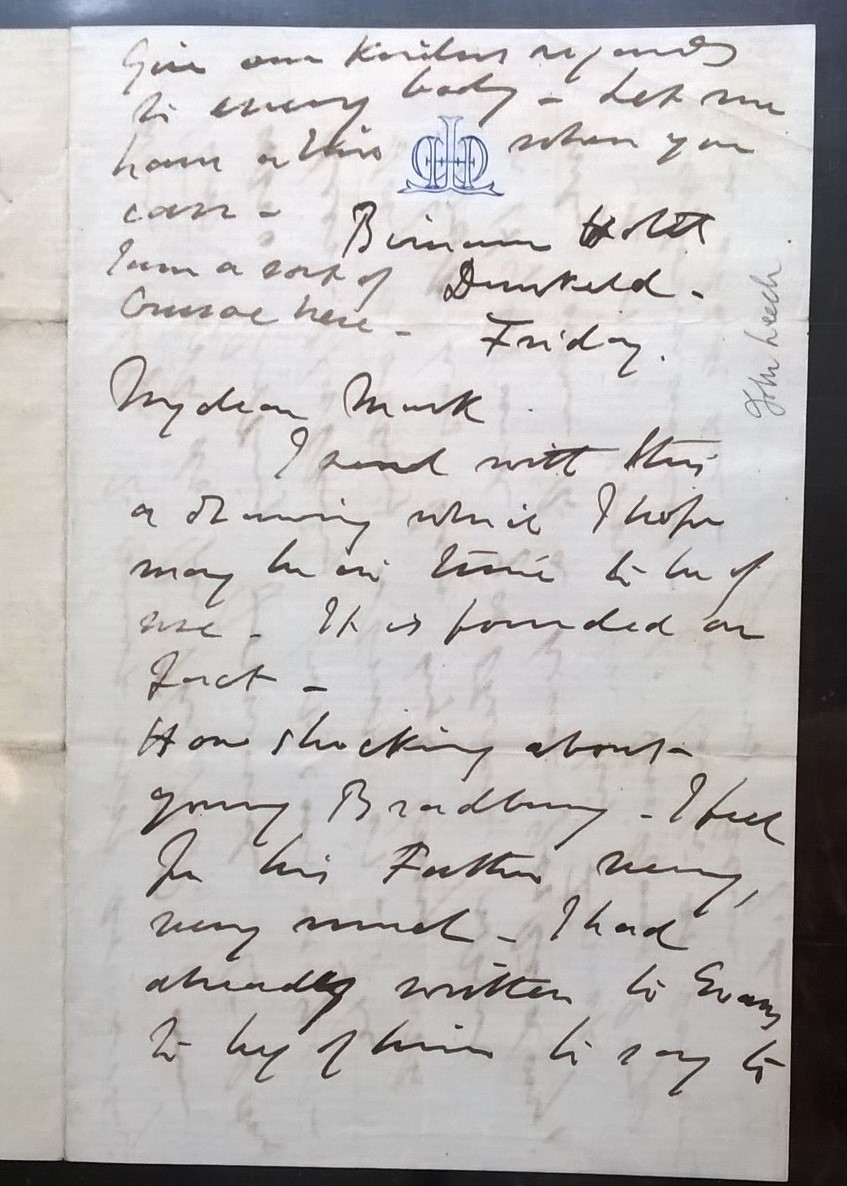

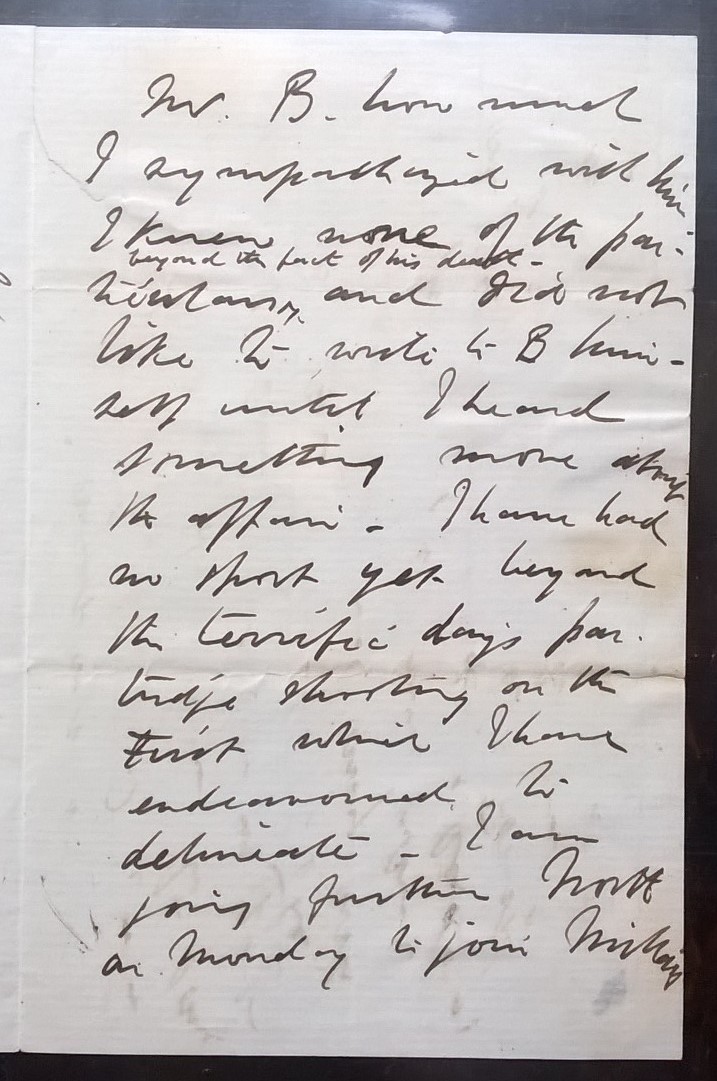

Letter from Punch illustrator John Leech to Punch editor Mark Lemon discussing (amongst other matters) the death of Henry Riley Bradbury. Author's own photograph.

Reverse of letter from John Leech to Mark Lemon discussing the death of Henry Riley Bradbury. Author's own photograph.

The reasons for Henry's suicide were, of course, known only to him. It may have been business matters, alcohol problems or affairs of the heart that were uppermost in his tormented mind. In his letter to Wills, Dickens reported that George Holsworth, a staff member on Dickens' All the Year Round had said that his suicide had been because of the unrequited love he had for one of Frederick Mullett Evans' daughters, who had recently married. This daughter would be Margaret Moule Evans (1837-1909) who had married Robert Orridge (1824-1865) on Tuesday 21 August 1860, eleven days before Henry's death. Dickens, who bore both William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans a great deal of ill will, also insulted both Margaret and Henry in the letter, and referred to Henry's "drunken mind", giving further credence to the rumours that he had a fairly well known problem with alcohol. As the news spread Punch caricaturist John Leech wrote to Mark Lemon from the Birnam Hotel in Dunkeld, Scotland, where he was holidaying, saying:

"How shocking about young Bradbury. I feel for his father very, very much - I had already written to Evans to beg of him to say to Mr. B. how much I sympathized with him. I knew none of the particulars beyond the fact of his death - and did not like to write to B himself until I heard something more about the affair."

Very little appeared in the newspapers regarding Henry's suicide. Dickens commented in the letter to Wills that he supposed "strong influence to have been used in that wise, to keep the dismal story quiet." A cryptic report appeared in the Exeter Flying Post of 12 September 1860 stating:

"A sadder story is told of a printing firm in the city: the son and junior partner of the concern having attempted suicide in Cremorne Gardens ... Extravagance and debt are said to be the causes of the catastrophe."

For a wonderful, in-depth exploration of Henry Riley Bradbury's printing career, please see the paper The life and craft of William and Henry Bradbury, masters of nature printing in Britain written by Adrian F Dyer. [57]

Three months later the postponed marriage of William and Sarah's second son William Hardwick to Laura Agnew took place at the parish church of St Mary the Virgin, in Eccles, Lancashire. [58] The occasion would undoubtedly have been rather a bittersweet one. The ceremony was witnessed by William and Sarah's youngest son Walter, their daughter Edith, William and Sarah themselves, Frederick Mullett Evans and Bradbury and Evans' former foreman printer Charles Hicks, with whom the Bradburys had maintained a deep friendship. William and Sarah became grandparents for the first time on 31 October 1862 when Laura gave birth to her and William Hardwick's first child, a son, whom they named William Lawrence Bradbury (1862-1953). [59] There followed more happy news for the family with the marriage of daughter Edith to Charles Swain Agnew (1836-1914), brother of William Hardwick Bradbury's wife Laura. [60] Edith and Charles married on Thursday 28 July 1864 at the parish church of St Pancras, London and set up home in Lancashire where the Agnew family were from. William and Sarah welcomed more grandchildren into the family; daughters Lilian and Mabel were born to William and Laura, and Edith and Charles had a daughter Edith Jessie and a son Charles Leonard.

As the 1860s progressed William Bradbury began to suffer from protracted periods of illness; he never fully recovered from the emotional trauma of son Henry's death. Bradbury and Evans' friend the author William Makepeace Thackeray died suddenly and unexpectedly from a stroke on 24 December 1863 aged fifty-two and the following October illustrator John Leech died aged just forty-seven. These two deaths came as a huge and profound shock to both William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans and their staff, causing immense sadness to all.

In the summer of 1865 William made his first visit in three years to the weekly Punch dinner. He was warmly welcomed back. He spoke of how grateful he was to be in somewhat better health and how he had never expected to be well enough to dine with his "dear old friends again." [61] By the autumn both William and Frederick were in agreement that the time had finally come to retire and their thirty-five year partnership was dissolved in November 1865. [62] A dinner was held at the Albion Tavern on Wednesday 1 November 1865 to mark their retirements, and to welcome their sons William Hardwick Bradbury and Frederick Moule Evans, who carried on the business trading as Bradbury, Evans and Co. After a toast to the new firm, Punch editor Mark Lemon stood and raised a glass to both William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans, who he movingly said had "weathered so many storms and brought their ship into harbour successfully at last." [63]

In the spring of 1869 William contracted another bout of bronchitis, which very sadly this time proved fatal. He died at his home 13 Upper Woburn Place, London, on Sunday 11 April 1869, two days before his seventieth birthday. [64] His death was registered three days later by his youngest son Walter, who had been present at his father's death. He was buried in the same plot as his son Henry in Highgate Cemetery on Thursday 15 April. A report in the South London Chronicle read:

"On the 15th inst., the mortal remains of Mr. W. Bradbury, the well-known printer and publisher, were interred at Highgate Cemetery. Amongst the mourners were his son, Mr. Wm. Bradbury; his partner, Mr. F. M. Evans, Mr. Mark Lemon, and several relatives, friends and workmen." [65]

A tribute to William in Punch magazine appeared on Saturday 24 April 1869. It read:

"Those who produce this Periodical desire that it should contain a record of their affectionate regard for one, who, at a good old age, and in possession of all the rewards due to an upright and energetic life, has just passed to his rest. MR. BRADBURY, from the early moment when he became associated with this Journal, devoted himself to its interests in a spirit of no mere commercial venture : he rejoiced in all its successes, and to contribute to them was at once to become the friend of a man with whom friendship was no idle name. His genial presence at the meetings of the Contributors was ever welcome, and his hearty co-operation in matters of business was not more appreciated by them than his avowed pride in the fortunes of the work, or his brotherly sympathy with all engaged upon it. They will not soon forget the good man, and good friend, who has peacefully passed away."

William's brother Orlando died on 7 December 1872 at the age of sixty-seven. [66] His deep and abiding love for music continued to the end of his life. He was secretary of the Noblemen and Gentlemen's Catch Club, and composed prize winning glees and ballads. [67] His obituary read:

"Mr. Orlando Bradbury, Vicar Choral of Westminster Abbey, with which choir he had been intimately connected for many years, died on Saturday afternoon at his residence in Pimlico. On Sunday afternoon the Rev. Canon Conway, in his sermon, most feelingly alluded to the loss sustained by the death of Mr. Bradbury. Out of respect to the memory of the deceased gentleman, the anthem was Sir John Goss's "Brother, thou art gone before us."" [68]

Sarah Bradbury outlived her husband by almost thirty years; tragically she also outlived her remaining two sons, William Hardwick and Walter. Walter, a civil engineer who had emigrated to Australia, died on 14 July 1891 [69] at the age of fifty-one. William Hardwick Bradbury died a little over a year later on 13 October 1892 at the age of fifty-nine. [70] There had been the joy of more grandchildren for Sarah following William's death; William Hardwick and Laura had had another little girl, Alice Hope Bradbury; Edith and Charles had had a son, Frank, and a daughter Mary Beatrice; and Walter and his wife Ellen had had a son, Charles and a daughter, Edith. Sarah Bradbury died on Christmas day 1898 at her home 2 Endlesham Road, Nightingale Lane, Clapham, at the age of ninety-five. [71] An obituary in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle on 29 December 1898 read:

"The death is announced of Mrs. Bradbury, Senior, widow of the late Mr. William Bradbury, of the eminent firm of Bradbury and Evans, printers and publishers, of Whitefriars. Mrs. Bradbury, who was in her ninety-sixth year, was intimately acquainted with a number of literary celebrities with whom her husband had relations in the way of business and of private friendship : and her clear memory was stored with recollections of Dickens, Thackeray, Jerrold, a Beckett, Leech, T. Hood, Mark Lemon, Horace Mayhew, and others. She remembered well the starting, in 1846, under Charles Dickens's editorship, of "The Daily News," with which journal the firm of Bradbury and Evans was closely associated, both as printers and joint proprietors : and it may be said generally that the most prominent members of the staff, both of "Punch" and "The Daily News," in those days were well known to her."

Sarah was buried in the same plot as her son Henry and husband William in Highgate Cemetery on Thursday 29 December 1898.

References

- ^ Silver, Henry. Diary entries 12 April 1865 and 11 April 1866. Punch Archive. British Library

- ^ Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Diocese: Diocese of Derby; Derbyshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932

- ^ Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Derbyshire Church of England Parish Registers; Diocese: Diocese of Derby; Reference Number: D 2057 A/PI 29

- ^ UK, Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices' Indentures, 1710-1811; Class: IR 1; Piece: 18 ; Master's Name John Bradbury; Apprentice Name John Meller; Residence Location Bakewell, Derby; Payment Date 7 Sep 1747

- ^ Glover, Stephen ed. by T. Noble, The history of the county of Derby, Volume 2 page 65

- ^^ Derbyshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812; Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Derbyshire Church of England Parish Registers; Diocese: Diocese of Derby; Reference Number: D 2057 A/PI 29

- ^^ Derbyshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812; Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Derbyshire Church of England Parish Registers; Diocese: Diocese of Derby

- ^ Lincoln St Mary Magdalene Parish Records - Marriages & Banns (1811-1812)

- ^ Stark, Adam 1810 The History of Lincoln: With an Appendix... page 282

- ^ Stamford Mercury 14 October 1808

- ^ Stamford Mercury 20 April 1832

- ^ Stamford Mercury 05 May 1820

- ^ Silver, Henry. Diary entry 26 January 1859. Punch archive. British Library

- ^ Spielmann, M. H. 1895 The history of Punch

- ^ Stamford Mercury 1 March 1822

- ^ Stark, Adam 1810 The History of Lincoln: With an Appendix... page 287

- ^ Stamford Mercury 3 May 1822

- ^ Stamford Mercury 15 November 1822

- ^ Yorkshire Grand Musical Festival, 1823 ... printed by W Blanchard, Chronicle Office page 10

- ^ Crosse, John 1825 An Account of the Grand Musical Festival, Held in September, 1823, in the Cathedral Church of York; for the Benefit of the York County Hospital, and the General Infirmaries at Leeds, Hull, and Sheffield ... page 307

- ^ Stamford Mercury 1 October 1824

- ^ Todd, William B 1972 A Directory of Printers and Others in Allied Trades London and Vicinity 1800-1840 p.23

- ^ London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921; Parish Register St Bride Fleet Street City of London, England; Marriage date: 4 Jun 1825

- ^ Stamford Mercury 11 April 1788

- ^ 1841 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 183; Book: 2; Civil Parish: Bakewell; County: Derbyshire; Enumeration District: 3; Folio: 38; Page: 10; Line: 12; GSU roll: 241289

- ^ Derbyshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932; Derbyshire Record Office; Matlock, Derbyshire, England; Diocese: Diocese of Derby; Reference Number: D 2057 A/PI 39

- ^ Stamford Mercury 28 July 1826

- ^ Stamford Mercury 21 December 1827

- ^ Morning Advertiser 20 November 1827

- ^ Stamford Mercury 26 October 1827

- ^ Morning Advertiser 09 September 1831

- ^ Stamford Mercury 7 February 1834

- ^ Stamford Mercury 24 October 1834

- ^ London, England, Births and Baptisms, 1813-1906; Name Orlando Philip Dent; Record Type Baptism; Baptism Date 7 Jun 1835; Baptism Place Westminster St John the Evangelist Westminster, England

- ^ Guildhall, St Bride Fleet Street, Register of marriages, 1834 - 1837, P69/BRI/A/01/Ms 6542/10

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, St Bride Fleet Street, Register of Baptism, P69/BRI/A/01/Ms 6541, Item 3

- ^ Northampton Mercury 23 April 1836

- ^ Morning Post 5 November 1836

- ^ Bell's Weekly Messenger 18 March 1843

- ^ Hampshire Advertiser 07 April 1838

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Saint Mary, Stoke Newington, Register of burials, 1813 Jan-1851 Dec, P94/MRY/037; Call Number: P94/MRY/037

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD 1837-1915 Death Index: Name Letitia Jane Bradbury; Registration Year 1839; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Hackney; Inferred County London; Volume 3; Page 118

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837-1915; Name Walter Bradbury; Registration Year 1840; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Hackney; Inferred County London; Volume 3; Page 135

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837-1915; Name Edith Bradbury; Registration Year 1842; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Hackney; Inferred County London; Volume 3; Page 190

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name Philip Bradbury; Registration Year 1856; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district Kensington; Inferred County London; Volume 1a; Page 72

- ^ Once a Week Mr Charles Dickens and His Late Publishers Volume 1, Number 1 July 2 1859

- ^ England & Wales, Free BMD 1837-1915; Registration Year 1858; Registration Quarter Apr-May-June; Name John Price; Registration District Bakewell; Volume 7b; Page 358

- ^ Morning Post 20 January 1849

- ^ Derbyshire Courier 28 August 1858

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name Jane Price; Registration Year 1859; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district Bakewell; Inferred County Derbyshire; Volume 7b; Page 380

- ^ Patten, R. (2012, October 04). Bradbury, Henry Riley (1829–1860), writer on printing. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online Edition.

- ^ The Examiner 31 March 1855

- ^ Bell's Weekly Messenger 08 September 1860

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index 1837-1915; Name Henry Bradbury; Registration Year 1860; Registration Quarter Jul-Aug-Sep; Registration district Chelsea; Inferred County London; Volume 1a; Page 100

- ^ West Middlesex Advertiser and Family Journal 08 September 1860

- ^ Dickens, Charles, Dickens: Letters (I-XII) Volume 9: 1859-1861 Pilgrim Edition, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, et al., Dickens letter to W. H. WILLS, 4 SEPTEMBER 1860 OFFICE OF ALL THE YEAR ROUND

- ^ Published in Huntia, A Journal of Botanical History, Volume 15 Number 2, 2015, Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

- ^ Manchester, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930; Name William Hardwick Bradbury; Marriage Date 6 Dec 1860; Marriage Place Eccles, St Mary, Lancashire, England; Parish as it Appears Eccles; Father William Bradbury; Spouse Laura Agnew; Reference Number L49/1/6/33; Archive Roll 533

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837-1915; Name William Lawrence Bradbury; Registration Year 1862; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district Hampstead; Inferred County London; Volume 1a; Page 502

- ^ England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973; Name Edith Bradbury; Marriage Dat; 28 Jul 1864; Marriage Place Old Church,Saint Pancras,London,England; Spouse Charles Swain Agnew; FHL Film Number 598349, 598350, 598351, 598352, 598353, 598354, 598355

- ^ Silver, Henry. Diary entry 21 June 1865. Punch Archive. British Library

- ^ London Gazette 14 November 1865

- ^ Silver, Henry. Diary entry 1 November 1865. Punch Archive. British Library

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name William Bradbury; Estimated Birth Year abt 1800; Registration Year 1869; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Pancras; Inferred County London; Volume 1b; Page 19

- ^ South London Chronicle 24 April 1869

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name Orlando Bradbury; Estimated Birth Year abt 1805; Registration Year 1872; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Age at Death 67; Registration district St George Hanover Square; Inferred County London; Volume 1a; Page 218

- ^ London Evening Standard 29 June 1868

- ^ Lancaster Gazette 14 December 1872

- ^ Australia Death Index, 1787-1985; Name Walter Bradbury; Death Date 14 Jul 1891; Death Place Queensland; Father's Name William Bradbury; Registration Year 1891; Registration Place Queensland; Registration Number B024266; Page number 2554

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name William Hardwick Bradbury; Registration Year 1892; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Age at Death 59; Registration district Wandsworth; Inferred County London; Volume 1d; Page 380

- ^ England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Name Sarah Bradbury; Registration Year 1898; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Age at Death 95; Registration district Wandsworth; Inferred County London; Volume 1d; Page 380