The Song of the Shirt - Esther's Story

Family Overview

- Mother: Margaret Stone (born circa 1787)

- Father: Richard James Rookwood (1786-1838)

- Husbands: Michael Byrne; William Bedell (circa 1804-1843); David Fitzgerald (circa 1811-1856)

- Known Children: Esther Bedell (1836-1844); Catherine Bedell (1838-1839); Margaret Bedell (1840-1842); William Jeremiah Bedell (1843-1903); Emma Fitzgerald (born and died 1851)

Introduction

On a cold December morning in 1879 in a small terraced house in the East End of London, England, a woman worn down by a life of grinding poverty, took a cord, tied it around a nail in her bedroom wall and hanged herself. [1] Her name was Esther and she was seventy-two years old. Esther had spent her life in Victorian London’s East End, living and working in appallingly squalid conditions as a seamstress. She was desperately worried that she was going blind; failing eyesight would have meant that she was no longer able to work. Afraid of becoming a burden to her recently widowed son, Esther took the heart breaking decision that Tuesday morning to end her life. It was a tragic end to what had been an almost unbearably hard life.

Intriguingly, thirty-six years earlier Esther had become the subject of a phenomenally successful poem, Thomas Hood's The Song of the Shirt. The poem, celebrated throughout the country, played a pivotal role in the early success of the satirical magazine Punch under proprietors William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans, causing sales to treble almost overnight. To this day the poem’s author, Thomas Hood (1799-1845), is known and acclaimed yet Esther, his inspiration, has been all but lost to the mists of time.

Early Years

The spring and summer of 1807 brought a rare hot and sunny few months to London. As the summer days eased into autumn, a young woman readied herself for the birth of her second child, no doubt relieved that the weather was turning cooler for the last few weeks of her pregnancy. Margaret Rookwood and her husband Richard already had a lively little toddler, Isabella (1806-1888), named after her paternal grandmother. Thrown headlong into parenthood, Margaret had been just over five months pregnant with Isabella when she and Richard had married at the church of St Leonard in Shoreditch in September 1805. [2] They lived and worked amongst a large Irish community in Cartwright Street, Whitechapel, a long narrow street with a collection of ramshackle courts running off on all sides.

Richard, barely out of his teens and working as a bricklayer, knew this chaotic, disadvantaged riverside neighbourhood like the back of his hand. His parents, James Rookwood (circa 1760-1827) and Isabella nee Aldridge (circa 1760-1827), still lived in Cartwright Square in one of the sixteen or so small houses that clustered at the bottom of Cartwright Street. This was where Richard and his four siblings had been born and raised. Some twenty-five years later in the midst of a cholera epidemic Cartwright Square would be brutally described as “a filthy and close neighbourhood”. [3] Their lives and those of the community were intimately intertwined with the bustling River Thames. London was a thriving port thronged with trading ships which, until the building of the docks, had arrived and departed from an assortment of woefully inadequate quays and wharves stretched out along the river. Ships laden with cargoes of luxuries such as tobacco, tea, coffee, cocoa, spices, sugar, rum, brandy, fruits and nuts could take several weeks for the labourers to unload. Unsurprisingly opportunistic and organised thieving gangs abounded in the area, with goods worth many hundreds of thousands of pounds being stolen from the laden vessels each year. Therefore a decision was taken by Parliament at the close of the eighteenth century to build a series of secure enclosed docks. The West India Docks were the first to be opened in August 1802, followed by the London Dock on 30 January 1805. This dock, surrounded by an enormous brick wall, was a mere five minute walk to the south east of Cartwright Street. As a bricklayer Richard had probably been involved in its construction. A multitude of skilled and unskilled local and immigrant workers depending on the River Thames for their livelihood lived cheek by jowl in the cramped mean streets around the docks eking out a meagre living.

Royal Mint Street (Rosemary Lane) showing the wall that once surrounded the Royal Mint. Author's own photograph.

Situated about half a mile to the east of Tower Hill, Cartwright Street also sat immediately off Rosemary Lane, now Royal Mint Street, which for over one hundred years had been home to the infamous unlicensed market known as the Rag Fair. Although primarily known amongst Londoners for the sale of second and even third-hand clothing, practically anything and everything, both legal and illegal, was sold, traded, pawned and stolen from Rosemary Lane.

In 1807 Richard and Margaret's neighbourhood was undergoing a period of enormous change as the new Royal Mint was under construction alongside Cartwright Street. The Royal Mint had originally been housed in the Tower of London, but the need for upgraded larger machinery had meant that it had out-grown its home there. In sharp contrast to its neighbours, the elegant new Mint building was taking shape on a five acre site, home for twenty years to tobacco warehouses, and for over two hundred years prior to that to the Royal Naval Victualling Yard before its removal to Deptford in 1785. Over the course of that hot spring and summer a host of stone masons, bricklayers, carpenters, joiners, plasterers and labourers had sweated and toiled over the construction of the new Mint. They had made excellent progress; the building had been roofed and preparations were well in hand for the demolition of a host of “shabby buildings”, in order to prepare a grand entrance way for the Royal Mint facing Tower Ditch. Mercifully that summer no catastrophic accidents had occurred at the build; the previous August a stonemason had been fatally wounded when a huge stone had fallen on him, smashing his legs. The poor soul had been transported by cart a long and painful mile to the London Hospital, later known as the Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel, but sadly on arrival had been beyond help. [4]

On Sunday 25th October 1807 Margaret Rookwood gave birth at home to a second daughter. The baby, a sister for Isabella, was given the name Esther. We have no record of the length or difficulty of her labour but it is highly probable that Margaret was helped and supported through the birth and early weeks afterwards by her female relatives and neighbours. The safe delivery of a live baby and the survival of the mother would have been an overwhelming relief to all who loved and cared for them. At the turn of the nineteenth century young women and their babies were sadly all too vulnerable to complications of the birth, and could die in the immediate days and weeks afterwards due to issues such as blood loss and postpartum infections. On 15th November 1807 Margaret and Richard had Esther baptised at the local church of St Botolph, Aldgate twenty-one days after her birth. [5]

New Crane Stairs at the bottom of New Gravel Lane (now Garnet Street), leading directly to the River Thames. Author's own photograph.

Two years later in December 1809 Margaret Rookwood was once again in the full throes of childbirth. This would be her third baby in three years. On 23rd December a third daughter was born and baby Louisa took her place in the family alongside her older sisters Isabella and Esther. [6] The Rookwoods had moved house and were now living a mile to the east of Cartwright Street, in a shared house at 118 New Gravel Lane just off the Ratcliff Highway in the parish of St Paul, Shadwell. New Gravel Lane (now Garnet Street), a long street lined with some eighty properties on each side, led from the High Street directly down to the damp and well-trodden stone steps of New Crane Stairs at the edge of the River Thames. It also lay a short six minute walk along Wapping Street from the site of grisly Execution Dock as shown on Richard Horwood's wonderful map published between 1792 and 1799.

For four hundred years Execution Dock on the bank of the Thames had been the site of the execution by hanging of miscreants convicted by the admiralty courts of murder, piracy, mutiny and high treason. At a trial at the Old Bailey six months before Louisa’s birth, Captain John Sutherland was found guilty of the appalling murder of his twelve year old cabin boy Richard Wilson. Whilst at sea the previous November, Sutherland, aged forty-five, had seized his knife in a fit of blinding anger and had viciously stabbed Richard twice in the stomach, ripping through his intestines. Sutherland was drunk and in a raging fury after reputedly having goods stolen by his crew. Two surgeons had been hastily summoned from a nearby ship to tend to Richard and to try to repair the terrible wounds he had sustained. The young boy lingered feverishly in agony, fatally injured for nine long days, before dying on 14th November 1808. After the sentence of death was passed on Captain Sutherland he became quite faint as the full realisation of his fate dawned on him. He had to be supported out of the court room back to prison by two companions. Six days later, on Thursday 29 June 1809 at a quarter-past eight in the morning, Captain Sutherland was taken from his cell at Newgate prison, placed in a cart and escorted through the streets from the prison to Execution Dock. The procession was headed up by sixteen Sheriff’s officers on horseback, with the City Marshalmen and a number of local constables bringing up the rear. Huge crowds lined the route, jostling and gossiping in ghoulish excitement, straining to witness the grim cavalcade as it clattered by en route to death. People leant from the open sash windows of their houses and balanced precariously on roof tops trying to secure the best possible vantage point for themselves. As his sombre journey progressed Captain Sutherland could be heard fervently muttering prayers. At Execution Dock the River Thames teemed with assorted boats and crafts, their crews all keenly hoping for a good view of justice being meted out. The Captain’s hands were tied and he was led out of the cart to the gibbet, erected at the low tide mark. After mounting the scaffold, he spent some moments in solemn prayer with the Rev Dr Ford, before addressing the hushed crowds. Astonishingly, Sutherland declared himself to be quite innocent of causing the death of Richard. He was firmly, if somewhat bizarrely, of the opinion that Richard’s death had been solely due to a lack of appropriate medical care from the two surgeons. He then handed his prayer book over to the hang-man, and was executed. He was left hanging in place for about thirty minutes following death, before, as the tide lapped about his feet, his body was cut down and taken away for medical dissection. It was not uncommon for bodies to be left hanging at Execution Dock until three high tides had covered them. Such was the neighbourhood in which Esther, Isabella and Louisa lived.

In December 1811 events occurred in and around New Gravel Lane that were to send shock waves reverberating around the country. Two families were brutally murdered late at night in their homes just twelve days apart from each other. The first murder took place on the night of Saturday 7th December at 29 Ratcliff Highway, the home and business of twenty-four year old Linen Draper Timothy Marr, his wife Celia, and their baby son Timothy who was just fourteen weeks old. Also living at the property was a fourteen year old apprentice, James Gowen and a young servant girl by the name of Margaret Jewell. Whilst Margaret Jewell was out that evening running a few brief errands for her employer, the Marr family and young James Gowen were slaughtered. Their skulls were smashed and their throats were cut in a senseless, frenzied act of violence.

The second horrific murder took place twelve days later, on Thursday 19 December at 81 New Gravel Lane just across the street from the Rookwood's lodgings. John Williamson (1756-1811) and his wife Catherine (nee Neighbour) (1751-1811), [7] publicans, had been relaxing in their kitchen after the day’s business at the King’s Arms public house, whilst their servant Bridget Harrington had busied herself making preparations for the morning. A very popular couple, the Williamsons were well known and admired in the parish. John had been a sailor before their marriage seventeen years previously. [8] It had been his first marriage but Catherine’s third. Catherine’s fourteen year old grand-daughter Catherine ‘Kitty’ Stillwell (born 1797) [9] was fast asleep in her bedroom on the second floor of the King’s Arms. Kitty and her family lived with the Williamsons. Her mother Ruth (nee Cudbird) had died when Kitty was six years old. [10]

At around twenty minutes past eleven the relative peace of the neighbourhood was fractured by an almighty ruckus. As people left their homes to see what was happening they were confronted by John Turner, the Williamson’s lodger, making his way precariously down tied-together bedsheets thrown from an upper storey window. He was screaming almost incoherently that there had been a murder. It emerged later that John had retired for the night and had not been in bed for more than about five minutes when he had been startled by the front door slamming loudly. Almost immediately Bridget Harrington had screamed out in alarm that they would all be murdered. Most distressingly, he had then heard two or three blows being struck, and John Williamson shouting ‘I am a dead man!’ Frozen in horror, John Turner had waited in the darkness too terrified to move for a few minutes, before cautiously creeping downstairs to the first floor. He then heard three heavy sighs and someone walking around on the floor below. Bravely he had continued down the stairs and by the light of a candle could make out the back of a very tall man bending over someone on the floor. Frightened half witless, John had turned and fled as quietly as he could back up the stairs. Once in his room, he had tied two sheets firmly together, flung open his window, thrown out the sheets, and lowered himself down to the street.

He was led away to the local watch house to give his story as shocked crowds amassed outside the King’s Arms. Thoughts must have leapt instantly to the dreadful slaughter of the Marr family just twelve days previously. Parish beadle George Cleugh entered the building and staggered out carrying Kitty Stillwell, who thankfully appeared to be physically unharmed. He immediately sent word for Mr John James Mallett, the Chief Clerk of Shadwell police, who arrived on the scene with two other officers. Soon the hideous truth emerged; John and Catherine Williamson and their servant Bridget Harrington were indeed all dead, butchered in a near replica of the Marr family murders.

For Margaret and Richard Rookwood with their three young daughters the fear and panic must have been indescribable. This most brutal of murders had happened on their doorstep to people they would have known well. Two year old Louisa, four year old Esther and almost six year old Isabella would undoubtedly have been affected by the terror and confusion of the adults around them.

By modern standards a very chaotic and haphazard investigation was carried out into the murders. Many people were arrested and taken into custody, but no conclusive evidence was found against anyone. On 21 December a twenty-seven year old sailor named John Williams was taken into custody following information. He lodged at The Pear Tree public house in Cinnamon Street, Wapping, a five minute walk from New Gravel Lane, and drank regularly in the King's Arms. He was a slight man who in no way matched the description of the suspect given by John Turner. Nevertheless he soon became the prime suspect despite only circumstantial evidence against him. He was remanded to Coldbath Fields Prison in Clerkenwell and was due to appear before the Shadwell Magistrates at eleven o'clock on the morning of 27 December. However, early that morning, he was discovered dead in his cell having apparently hanged himself. His supposed suicide was taken as proof of his guilt, and investigations all but ceased, even though at least two people were believed to have been involved in the murders. As it was felt that Williams had escaped justice by killing himself, the Home Secretary ordered that his body be paraded through the local streets so that residents could see for themselves that the depraved perpetrator was dead.

Illustration showing the body of John Williams outside the King's Arms, New Gravel Lane. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Marriage to Michael Byrne

The years passed and Esther and Isabella grew to adulthood. Their mother Margaret and younger sister Louisa sadly seem to disappear from the records, and I feel they must have died at some point before the early to mid 1830s. Over the intervening years Esther had moved the short distance back towards the streets of her birth, and by the summer of 1832, when she was twenty-four years old, she was living in the parish of St Mary, Whitechapel. On Sunday 29 July 1832 at the parish church of St Mary Matfelon, Esther married. Her new husband was a man by the name of Michael Byrne [13] Michael was literate signing the marriage register in his own neat hand; in contrast Esther who couldn't read or write, simply placed a cross by her name, as did their two witnesses Patrick Byrne and Eliza Langdon. Patrick may have been Michael's father, and if so Michael was born into extremely difficult circumstances. A baptism record from the church of St Mary Matfelon, for a Michael Burn born to Patrick and Mary in 1801, records that the family were poor and living in the workhouse. [14] Patrick and Mary had also had another son, James, baptised at the same church in February 1797 and again they were recorded as living in the workhouse. This workhouse had been constructed in 1768 on the site of a former burial ground on Whitechapel Road. [15] A report on the workhouse from a physician in 1838 makes for rather grim reading: "I was likewise struck with the pale and unhealthy appearance of a number of children in the Whitechapel workhouse, in a room called the Infant Nursery. These children appear to be from two to three years of age; they are 23 in number; they all sleep in one room, and they seldom or never go out of this room, either for air or exercise...The privies in this workhouse are in a filthy state, and the place altogether is very imperfectly drained: there is not a single bath in the house." [16]

Esther and Michael would have begun their married life in the streets around Whitechapel, unfortunately we have no record which streets they lived on or how Michael earned a living. Esther's sister Isabella also had a partner, Richard Haynes (1806-1838), and although unmarried, she and Richard lived together presenting themselves as husband and wife. They lived in a house directly by the River Thames abutting the colossal wall of the London Dock [17] in Salter's Alley, Green Bank, Wapping. Their families had known each other since the two were babies as Richard had been born in Crown Court, one of the small squares directly across the street from Esther and Isabella's first home in Cartwright Street. [18] By that summer of 1832 Isabella had given birth to three children: a daughter Isabella born 1827, a son Richard born 1829 and a daughter Mary Ann born 1831.

What happened next with Esther and Michael is a complete mystery; he seems to disappear without a trace. I believe he died, however there remains the possibility that he may have left Esther or that Esther may have left him, I cannot establish the truth with any certainty. What we do know is that three years after her marriage to Michael, Esther married again and was recorded as being a spinster. [19]

Marriage to William Bedell

The parish church of St Leonard, Shoreditch, where Esther and William Bedell married, as it appeared in 1816. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

As the dry and humid London summer of 1835 gave way to autumn Esther, now aged twenty-seven, prepared to marry for the second time. She was marrying William Bedell, a dock labourer and sometime seaman in his early thirties. He was not British and I believe he may have been an American, possibly from New York. They married on Sunday 20 September 1835 at the parish church of St Leonard, Shoreditch, [19] and were both living in the parish, just over a mile away from where Esther and Michael Byrne had married. William was a bachelor and was literate, signing his own name. Esther was recorded in the parish register as a spinster, although her name was given as Esther Byron, which was most probably a misspelling/mishearing of Byrne. As she didn't give the name Rookwood this could indicate that her first husband Michael had died and that the recording of her as a spinster was a clerical error. She once again marked her name with a cross, as did one of their witnesses Catherine Twist.

Esther quickly became pregnant and the couple moved right back to the heart of London's dockland and the streets of Esther's birth. Esther would spend the majority of her life in this area, moving a few streets one way and then the other. They found cheap lodgings in a room on Glasshouse Street (now John Fisher Street), off Rosemary Lane, two or three streets away from Cartwright Street and immediately by London Dock. They and their neighbours had a strong sense of community, but were poor with many of the men earning a meagre living by hard physical work around the docks and the River Thames as labourers, coal-whippers, stevedores and lightermen, subsisting in quite desperate conditions. The neighbourhood was overcrowded, cramped, narrow, dark and dangerous. These surroundings gave rise to tensions and provided an excellent cover for thieves and other criminals. The alleys often rang with rowdy, drunken disputes and violence. On Cartwright Street in the summer of 1833 a man had thrown a brick in anger at his neighbours, killing a four-month old baby being nursed in its mother's arms. [20] Many of the dilapidated houses and tenements had broken windows or lacked them altogether and some were only partially roofed. It was not unheard of for loose tiles to fall from roofs or even for entire buildings to suddenly collapse without warning. Rooms had dirt-floors and proper drainage was all but non-existent. The stench from the unpaved streets must have been unbearable as they ran with filth from both humans and animals. Infection and disease were rife.

In stark contrast to these miserable, decaying alleyways, a magnificent gin palace had been built on Rosemary Lane a few years earlier. It shone with modern gas lamps, mahogany fixtures and fittings, and brightly coloured casks of liquor. On the outside was an elegant lamp which had cost one-hundred guineas and a clock which was illuminated after dark; for any locals going inside it must have been like entering another world. [21]

On Monday 25 July 1836 Esther gave birth to her first child, a daughter whom they named Esther. Little Esther was baptised at the church of St Mary, Whitechapel on 11 November that same year. [22] Esther and William then moved a street westwards and by the winter of 1838 were living at 10 Braces Buildings at the south end of Blue Anchor Yard. Conditions in Blue Anchor Yard were dire. An open gutter full of stagnant putrefying matter ran through the middle of the yard, and the area was filled with buildings in various states of disrepair clustered into a disorderly mass of claustrophobic courts. Filth and disease were everywhere and to outside observers it seemed impossible for air to penetrate this squalid and oppressive neighbourhood. [23] Into this desperate chaos Esther and William's second daughter, Catherine, was born on Thursday 29 November 1838.

About a mile away in Wapping, Isabella had also recently given birth. That summer she and Richard had had a daughter Nancy, who joined the three oldest children and their two other children, a daughter Emma born in 1833 and a son James born in 1835. Isabella's partner Richard worked as a Carman, transporting goods from the docks via a horse drawn vehicle. To supplement their income Isabella made umbrellas and parasols, possibly working for a Mr Black who was an umbrella maker on Wapping Street very close to their home. [24] However in December 1838 Richard became seriously unwell with typhus fever, an infectious disease transmitted from person to person by body lice. Very sadly Richard died from the illness in their overcrowded lodgings on 11 December 1838 at the age of thirty-two. Tragically, but unsurprisingly, Isabella and their young children had also been bitten by lice and infected with typhus. On the same day that Richard died they were all admitted to the St George in the East workhouse. The workhouse admission and discharge register recorded that Isabella had been "burdened with a large family of illegitimate children". The sheer awfulness of this dreadful time became even worse. Esther and Isabella's father Richard Rookwood developed a 'brain fever' at his home on Upper Grove Street. Distressingly, just ten days after the death of Richard Haynes and the admittance of Isabella and the children to the workhouse, Richard Rookwood died at his home from his illness aged fifty-two. [25] Esther sat with him as he died.

In the bleak and wintry early months of 1839 Esther and William's baby daughter Catherine struggled to survive. On Wednesday 6 March Esther and William were so fearful for her survival that they called the parish priest to their home to have Catherine baptised privately. [26] Very sadly their worst fears were proved correct and she died the next day; the cause of death was given as 'decline'. [27]

Isabella and her children were also struggling. She had been in and out of the workhouse in the weeks following her partner's death as she tried desperately to make ends meet and care for the children. In January 1839 two of her daughters, Mary Ann and Emma, had been sent by the workhouse to Mr Drouet's Establishment for Pauper Children in Tooting, where they received a little formal eduction and worked at menial jobs. They remained there until 4 March, when they were returned to their mother. A day after her little niece Catherine's death, Isabella and the children were once again admitted to the workhouse. The three oldest girls were again sent to Mr Drouet's establishment, whilst Isabella and children James and Nancy remained in the workhouse. Most horribly on 20 March James died aged four, swiftly followed by his little sister Nancy who died four days later aged just seven months. Within a period of seventeen days Esther and Isabella had suffered the unutterably awful tragedy of the loss of three of their children. On 29 April Isabella requested the return of her surviving daughters from Tooting and then discharged herself and the girls from the workhouse. There is a poignant note in the records which states that Isabella left with shoes, bedding, a blanket and rug and that the children were allocated some clothing.

Following Catherine's death Esther, William and their daughter Esther moved home again, this time to lodgings three streets eastwards on Well Street (now Ensign Street). Including themselves there were eighteen people living in the house. [28] Esther soon became pregnant again, and a third daughter, Margaret, was born on Monday 5 October 1840.

Well Street, now Ensign Street, taken in August 2018. The black cast iron bollards, which are marked with the monogram RBT, mark the frontage of the Royal Brunswick Theatre which collapsed three days after opening. The site then became the Sailors' Home. Author's own photograph.

Their lodgings were opposite the 'Sailors' Home'. Opened in May 1835 on the site of the Royal Brunswick Theatre, which had collapsed killing ten people a mere three days after opening in February 1828, the Sailors' Home sought to provide comfortable, affordable board and lodging for around one-hundred sailors. By June 1840 the home had been fitted-out with berths to accommodate one-hundred and seventy-five sailors each paying fourteen shillings per week, and the building itself was thought to be capable eventually of housing around four-hundred and fifty men. The founders of the home hoped that their institution would save the sailors from "the contaminating influences to which they are at present unavoidably exposed in the existing boarding houses." Unfortunately many sailors were left without money for up to ten days after arriving in port, as their wages were held until the ship's cargo had been unloaded. Ready to exploit these sailors were men known as Crimps, who would either advance the sailors money or cash existing wage advances at a discount. The Crimps would pay watermen to bring them sailors from the ships. The sailors would then be steered towards the Crimps' own lodging houses, public houses, goods and service providers, who would charge the vulnerable men exorbitant rates and defraud them of as much of their money as they possibly could. The Well Street Sailors' Home tried to prevent sailors from falling victim to these unscrupulous Crimps. House rules were strict and included no swearing or improper language; drunkenness was absolutely prohibited; quarrelling and abusive language discouraged; and a respectful manner to all staff was expected. [29]

Esther and William were also living alongside towering sugar refineries which were dotted throughout London's east end. Well Street and adjacent Dock Street each had at least one sugar refinery. These low-ceilinged seven to nine-storey structures dominated the immediate locality; at night their walls became a makeshift home to the homeless who sheltered against their heated sides. The streets of Whitechapel would have reverberated day and night with the sounds of this industry, the clatter of the arrival of hogsheads containing the raw product newly arrived into port, and the removal of the finished goods.

Towards the end of 1841 Esther, William and the children moved again. Their new lodgings at 68 Rosemary Lane in the heart of Rag Fair, were literally around the corner from their lodgings on Well Street. Meanwhile life had taken a turn for the better for Isabella. On 10 March 1840 at the church of St Leonard, Shoreditch, she married a mariner named James Crutchley (c.1803-1857). James was widowed and Isabella said that she too was a widow, despite not having married Richard Haynes. She gave her father's name as Richard Williams a bricklayer, and she had found work as a servant. She and James moved into lodgings in Braces Buildings, in the squalid Blue Anchor Yard two streets away from Esther and William. [30] In the autumn of 1841 Isabella gave birth to a son, Henry William Crutchley. Most awfully the sisters were yet again to face the death of their children within a few weeks of each other. Little Henry William died at just a few weeks old at the beginning of 1842, and then Esther and William's little daughter Margaret died at home on 8 April 1842 aged eighteen months from inflammation on the chest. [31] Following these dreadful losses both families moved home; Isabella and James to Darby Street, one street westwards, and Esther and William back to lodgings on Well Street.

Esther's Arrest

This enormous wall on Pennington Street is the wall that once surrounded the London Dock. Author's own photograph.

Esther soon became pregnant for the fourth time. William continued to work on and around the River Thames and the London Dock, being sometimes described in records as a dock labourer and in others a mariner. On the afternoon of Friday 6 January 1843 he was working on board a ship called the Mary which was moored in the East London Dock. He and ship's mate Robert Barrett were hard at work loading sacks of biscuits down into the ship's hold. William lowered down a bag and then walked around the raised section of the deck above the hold. As he did so he slipped and fell about ten feet into the hold, striking his head against a wooden beam as he fell. He was briefly knocked unconscious, but quickly came to and appeared to those who rushed to help him to be not too badly injured. In fact he appeared so little injured that he walked almost a mile to the London Hospital, where he was advised to get undressed and get into bed. However things soon took a huge turn for worse and William quickly became very unwell. Tragically he died within a few hours of reaching the hospital. He was thirty-nine years old. [32] A post mortem later showed that he had in fact fractured his skull in the fall. [33]

The devastation that William's death must have caused to Esther cannot be fully imagined. She was thirty-five years old, approximately eight months pregnant and without the means to support herself, daughter Esther and the imminently expected new baby. On Sunday 5 February 1843, almost a month to the day since William's death, Esther gave birth at their lodgings, 19 Well Street, to a baby boy, William Jeremiah Bedell. [34]

Esther's situation was now utterly dreadful. She needed basics such as food, shelter and heat; she and the children were living in a small sparsely furnished room in a shared house. Despite her desperation Esther seems to have had a fierce determination to keep herself and the children from being admitted to the workhouse; I wonder if Isabella's experiences in the workhouse a few years previously were a contributing factor in this. In a courageous attempt to keep her family together Esther began working as a seamstress sewing boys' trousers for Mr Henry Moses of 87 Tower Hill, a slop-seller who sold cheap ready made clothing. Since the late seventeenth century Esther's home streets had been synonymous with the clothing trade. Esther would have probably laboured at her sewing for around twelve to fourteen hours each day, maybe even up to eighteen hours a day in the lighter summer months. For each pair of boys' trousers that she made Esther was paid only 7d. From this meagre amount she had to purchase the cotton with which to sew the garments and candles in order to be able to see to sew. In the darker winter months the cost of the candles alone could amount to 10d or so each week.

The Song of the Shirt by William Daniels (1813-1881), inspired by Thomas Hood's poem of the same name. 1875 Oil on canvas 43.5 x 34.5 cm (17 1/8 x 13 9/16 inches) Picture courtesy of The Crowther-Oblak Collection of Victorian Art and and the National Gallery of Slovenia and the Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway via http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/daniels/1.html

Esther struggled her way through the spring and summer months of 1843, trying to eke out her money to keep a roof over their heads and food in their stomachs. However, it proved impossible. For more than a century impoverished people in Esther's and the surrounding neighbourhoods had used not only their own clothes, boots and shoes but sometimes stolen clothing, as items of trade and exchange. [35] Close to starvation, Esther turned to the local pawnbrokers and began pawning some of the boys' trousers as she made them in exchange for money to buy food. For a while she went undetected by her employer. Eventually, however, word of her illegal activity spread, and Esther was taken into custody. On Wednesday 25 October 1843 a "wretched-looking" Esther, nursing a "squalid half-starved" baby William, appeared before magistrate Mr (later Sir) Thomas Henry (1807-1876) at the local police court on Lambeth Street. [36] Lambeth Street no longer exists, however it was situated between Leman Street and Gowers Walk, a short five minute walk from Esther's lodgings on Well Street.

Esther was distraught. As the evidence against her was presented to Mr Henry she wept. Her life must have seemed so utterly bleak at that point. She had suffered the loss of so many loved ones in the space of just five years; her father, two daughters, two nephews and a niece, and of course her husband. She was facing the very real prospect of the deaths of her two surviving children, and was now also facing a prison sentence. Mr Henry questioned her and she told him about William's accident in the docks and his subsequent death. She explained how she had tried her utmost to work to support herself and the children, but that the pay was just too little to survive on. She related how she had pawned the trousers out of sheer hopelessness, in order to buy dry bread to eat. Somebody present in the court who knew Esther remarked that her lodgings were "the very picture of wretchedness." She had barely any furniture at all and the residence was described as being quite unfit for human habitation.

Mercifully Esther got a sympathetic hearing. Mr Henry appears to have been moved by her plight and incredulous at the money she was paid. After lamenting the fact that it was all too common an occurrence that women such as Esther pawned the clothing they were making, he stated that because the pittance they received was simply inadequate to subsist on, they were practically compelled to do so in order to survive. He asserted that, strictly speaking, he was bound to send her to prison. He went on to say that the workhouse would have been by far the best place for Esther and the children, and in her efforts to avoid being admitted she had got herself into her present difficulties. Swallowing her pride and clutching at this lifeline, Esther said that if she was allowed to go to the workhouse with the children then she would do so. Mr Henry stated that it would be a much better option than sending her to prison, and directed that a court officer should take her and the children to the workhouse immediately. [36] What must her emotions have been? She had been spared prison, but had ended up in the workhouse which she had fought so desperately to avoid. She must have felt so utterly beaten and exhausted from the sheer relentlessness of trying to hold everything together for so long.

Thomas Hood and The Song of the Shirt

The facts of Esther's court appearance were written up in the newspapers. A full account of the proceedings, together with an outraged and anti-Semitic commentary against her employer Henry Moses, appeared on page four of The Times newspaper on Friday 27 October 1843. Part of the commentary read: "And now what is to be done? Are we to fill our columns day after day, week after week, with appeals for the poor, and to find the only result in sympathetic letters and a few straggling 5l and 10l notes sent to the poor boxes of the police offices?"

The following Tuesday on page three of The Times a letter was printed from Henry Moses. It began "Having been personally attacked in a leading article of your widely-circulated paper of the 27th inst., and being classed with a people somewhat intemperately singled out for vituperation, I trust it will not be considered too much to ask space in your columns for my individual justification." After pointing out that out of upwards of forty wholesale slop-sellers in London, only three were of the Jewish community, he went on to say that his "allowance for labour is considerably higher than many of the most respectable outfitting warehouses in this metropolis. The boys' trousers, for making which I paid the woman Bedell 7d per pair, I sell at 2s 9d, which the price of the material being deducted, leaves me a profit varying from 5 to 7 ½ percent." Later he explained "I am one who would rather increase than diminish wages; a long practical knowledge having convinced me, that were wages increased to a living medium for the labourer my profits must rise with them. But, surrounded by a competitive market, I am compelled to sell as cheaply as my neighbours; and the prices I obtain seldom realize 7 ½ and very frequently fall short of 5 per cent profit."

Below his letter The Times wrote a response, part of which read "He may be, perhaps he is, the most liberal of all the slopsellers ... but it is not less true that his profit, whatever may be its amount, is the result of his availing himself of the necessities of extreme poverty; that by how much his drudges receive less than an adequate return for their labour, by so much his profit is, morally speaking, unjustly acquired."

A chord was struck. On Saturday 4 November 1843 under the heading "FAMINE AND FASHION", the weekly satirical magazine Punch reprinted The Times article concerning Esther's arrest, followed by an emotional outburst towards the slop-seller who would pay a worker the equivalent of one penny an hour. Taking an active interest in the debate was poet and writer Thomas Hood (1799-1845). He had read the original article in The Times and had been deeply affected by Esther's plight. Taking up the cause, Hood was inspired to write a poem highlighting the dreadful life of a seamstress such as Esther. He named this verse The Song of the Shirt. The opening stanza read:

"With fingers weary and worn, With eyelids heavy and red, A woman sat in unwomanly rags, Plying her needle and thread – Stitch! Stitch! Stitch! In poverty, hunger, and dirt, And still with a voice of dolorous pitch She sang ‘The Song of the Shirt!"

Later lines read:

"Work—work—work! My labour never flags; And what are its wages? A bed of straw, A crust of bread—and rags. That shattered roof—and this naked floor— A table—a broken chair— And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank For sometimes falling there!"

Hood submitted his poem to the editors of three publications, all of whom rejected it. As a last resort he sent it to Mark Lemon (1809-1870), editor of Punch magazine, with a note apologising that the subject matter would be ill-suited for use in a comic journal. He said that the poem could be thrown away if Lemon did not think it suitable for publication. Mark Lemon did decide to publish, and The Song of the Shirt appeared anonymously in Punch on Saturday 16 December 1843. It proved to be an absolute phenomenon. The circulation of Punch trebled as people clamoured to read it and letters poured in to the editor. The poem was spoken of country-wide in newspapers, was soon translated into different languages, it was turned into songs, captured in paintings and in a play The Sempstress: A Drama by Mark Lemon, it was even printed on cotton pocket handkerchiefs. It spread "through the land like wild-fire". [37]

Illustration A Startling Novelty in Shirts by John Leech published in Punch in July 1853. The shirt, covered with skeletons, highlights the starvation wages paid to the seamstresses who made it. Author's own photograph

However, conditions sadly remained utterly dismal for seamstresses for decades. In 1849 a seamstress said to playwright and journalist Henry Mayhew (1812-1887), "I live mostly upon coffee, and don't taste a cup of tea not once in a month, though I am up early and late; and the coffee I drink without sugar. Look here, this is what I have. You see this is the bloom of the coffee that falls off while it's being sifted after roasting; and I pays 6d. for a bagfull holding about half a bushel."

After the Workhouse

By the February of 1844, four months after her court appearance, Esther had left the workhouse and was living with Isabella and her family at 7 Darby Street, the street next to her birth street. Isabella had given birth to another son, Edward, eleven days before Esther had appeared in court. Very sadly, as if she hadn't faced enough, Esther was to experience the very worst that life could send yet again. Her seven year old daughter Esther was seriously unwell. She ultimately died from dropsy or oedema as we would call it today, at Isabella's home on 19 February 1844. Esther was with her when she died, and registered the death of her first born child seven days later. [38] I wonder if malnutrition played a role in her death. How would one continue on after all Esther had been through? It must have taken all of her strength and courage just to keep putting one foot in front of the other each day.

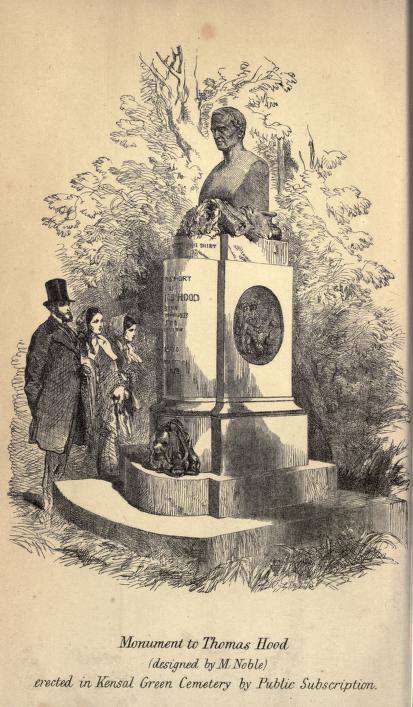

Illustration of the memorial erected to Thomas Hood in Kensal Green Cemetery in 1854. Illustration taken from Frontispiece to volume II of Memorials of Thomas Hood edited by F F Broderip and T Hood 1860.

She continued to work as a seamstress, as did her sister Isabella. On 3 May 1845 The Song of the Shirt author Thomas Hood died at his home after a long illness; he was forty-five years old. Hood's personal finances had been in quite a parlous state near to his death, and he was buried on 10 May 1845 at Kensal Green Cemetery, London with no headstone to mark the site. More than seven years later in the autumn of 1852 writer Eliza Cook (1812-1889) raised the fact that Hood had no grave monument. In November 1852, under the title A Tomb for Hood, Punch published a poem about this lack of a tombstone; the opening verses read:

"GIVE HOOD a tombstone; -'tis not much to give To one who stirr'd so oft our smiles and tears; But why a tomb to him whose lines will live, His noblest monument, to after years? To which I answer, that in times to come- Times of more equal lots and gentler laws- The workers may not seek, in vain his tomb Who pleaded, once, so movingly their cause."

The Sunday Times of 7 November 1852 carried an article calling for the same, stating that a number of young men of the Whittington Club were hoping to raise a monument or statue to Hood by public subscription. This club, with premises on Arundel Street, Strand, had been founded by Punch writer Douglas Jerrold in 1847. It was begun with a library, reading, meeting and dining rooms for the lower middle classes such as clerks working at the Inns of Court, shop assistants and journalists, and most unusually for the times women were permitted to be full members.

Donations in Thomas Hood's memory poured in and on 18 July 1854 the memorial was unveiled at Kensal Green Cemetery. The monument, topped with a bust of Hood, was sculpted by Matthew Noble (1817-1876) and contained two bronze reliefs illustrating his poems The Bridge of Sighs and The Dream of Eugene Aram. The inscription beneath the bust read "HE SANG THE SONG OF THE SHIRT".

Marriage to David Fitzgerald

As the year 1849 drew to a close, a new chapter opened in Esther's life. On Monday 10 December 1849 at the church of St Mary, Spital Square (formerly Sir George Wheler's Chapel), Esther, by now forty-two years old, married for the third time. Her new husband David Fitzgerald, was a thirty-eight year old widower. [39] It would seem from parish records that David's full name was Absolom David Fitzgerald, but he appears to have gone by the name of David. David was working as a fish seller, and both he and Esther were living at 11 Braces Buildings at the south end of Blue Anchor Yard. David had been left with young children following the death of his first wife Sarah, and so Esther became step-mother to at least four children: Thomas, William, Alfred and Sarah. Around this same time Esther's sister Isabella became a grandmother for the first time at the age of forty-three, when her eldest daughter, Isabella, gave birth to an illegitimate son Joseph William John Rookwood on 20 September 1849. [40] Isabella junior and her son moved in with Isabella and the family at 7 Darby Street.

Depressingly, Esther's living conditions remained abysmal. One year previously conditions in Hairbrain/Harebrain Court at the top end of Blue Anchor Yard had been beyond awful; Darby Street where Isabella and her family were living abutted this court. Following a cholera outbreak it was found that "the whole of the court (was) in a most filthy and disgusting condition, fish, soil and offal-refuse of various kinds, being strown about the surface. The paving of the court, which is pebble, has still more favoured this condition, by retaining in its hollows the liquids and smaller portions of offensive matter." The report continued: "At the back of the house, No. 7, on the right-hand side of Blue Anchor Yard, there are five privies in small yards discharging into three large cesspools immediately underneath. The privies are without seats, and the flooring, in places, is broken. The cesspools are full and overflowing into the yards. Soil and offal are scattered about the yards ...The emanations given off are most offensive and almost overpowering." There were thirteen houses in the small court, containing thirty-two rooms and which housed one hundred and fifty-seven people. It was found that many of the courts in the vicinity were sadly in a very similar condition. In Blue Anchor Yard large numbers of pigs were kept and residents had to live and work alongside a huge dung heap. [41] A few months before Esther and David's marriage a twenty-nine year old female fruit-seller had died of cholera at her home in Blue Anchor Yard, which was described as a filthy neighbourhood. The poor woman had apparently eaten large quantities of unripe fruit and had sat at her stall for hour after hour in all weathers. [42] In October 1849 a room in a 'penny lodging house' in Blue Anchor Yard was described in a court case: "It was a very small one, extremely filthy, and there was no furniture of any description in it. There were 15 men, women and children lying on the floor without covering. Some of them were half naked. For this miserable shelter each lodger paid 1d. The stench was intolerable, and the place had not been cleansed out for some time. It was also stated that several cases of cholera had occurred in the house and the adjoining ones, which were equally filthy." [43]

Around five months after her marriage to David, Esther became pregnant for the fifth time. A little daughter, Emma Fitzgerald, was born on Sunday 23 February 1851 and baptised at the church of St George in the East a month later. [44] On the census taken the night of Sunday 30 March 1851, the family are shown living at 12 Blue Anchor Yard. David was working as a fish hawker, Esther as a seamstress, David's son Thomas was a servant and his son William was a scholar. [45] I have been unable to find where Esther's son William Jeremiah Bedell was on the night of this census; he was definitely still alive.

Sadly yet again Esther had the most awful burden of nursing her little one as she died; baby Emma lived for only a few weeks, dying on 18 May 1851 at home from pneumonia. Esther registered the death six days later. [46]

In November 1853 there was good news for the wider family as Isabella's daughter Mary Ann married at the church of St Mary, Whitechapel. Her husband, Richard Morris worked as a carpenter, and both he and Mary Ann were living on Rosemary Lane. Mary Ann and her sister Isabella sometimes used the surname Rookwood and at other times the surname Haynes. The parish register records her surname as Haynes and gives her father's name as Richard Haynes, a bricklayer. It was actually her grandfather Richard Rookwood who had worked as a bricklayer. She was literate and signed her own name in a very neat hand, as did her sister Isabella who was one of the witnesses to the marriage. [47]

Regrettably another huge wave of sadness was on the horizon for Esther. Her husband David, who had been working as a dock labourer, became unwell around the year 1855 with liver problems. He died on Thursday 4 September 1856 aged forty-six from hepatic dropsey at their lodgings at 8 Braces Buildings, Blue Anchor Yard, the same building in which Esther's tiny daughter Catherine had died seventeen years previously. Esther was with David as he died, and registered his death the following day. [48]

Later Years

Life continued. Once again Esther had little alternative but to keep labouring away as a seamstress to provide enough money for food and lodgings. It would seem that she had developed a close relationship with her step-children. Sarah married on 14 October 1860 at the church of St Mary, Whitechapel. Her new husband, Thomas Cranmer Gordon (1838-1928) worked as a glass writer, and was the son of Richard Cranmer Gordon (1803-1845) a surgeon. Thomas' grandfather Joseph Cranmer Gordon (1766-1851) was raised by Henry Cranmer Esq at Quendon Hall, a magnificent grade 1 listed mansion set within a seventeenth century deer park on the edge of the village of Quendon in Essex. He may actually have been Henry Cranmer's illegitimate son; a greater contrast with Esther's history would be hard to imagine! One of the witnesses to the marriage was Esther, who placed her mark against her name. The other witness was Sarah's brother William, who also placed his mark. Sarah was literate, signing her own name. [49] The following March at the same church as his sister Sarah, William married Thomas Cranmer Gordon's sister Emily. Neither William nor Emily were literate. [49]

Isabella had also been widowed. In May 1857, eight months after David Fitzgerald's death, Isabella's husband James Crutchley had died at the age of fifty-four. [50] She and her unmarried daughter Emma also worked as seamstresses, scraping a living sewing trousers just as Esther did. Son Edward worked on the docks as a labourer. [51] Esther moved back to the street of her birth, finding lodgings at 69 Cartwright Square, where she boarded with Thomas Fenwick, a fish porter, and his family. [52]

In December 1867 Esther's thirty-eight year old widowed step-son Thomas Fitzgerald married again. He was working as a labourer and at the time of the marriage was living with Isabella and her family at 7 Darby Street. He married a widow by the name of Hannah Burrell (nee Lombard), and Esther was one of the witnesses to the marriage, placing her mark against her name. [53]

What of Esther's son William Jeremiah Bedell? The first definite reference that I can find to him after the court case in October 1843 when he was described as a squalid half-starved infant, is twenty-five years later at his marriage. William married a twenty-three year old Irish girl named Ellen Sullivan (1845-1879). I wonder if he was sent away as a 'nurse child' to be raised by someone other than Esther given her dire circumstances at the time of his birth. He probably went away to school and might even have spent some time at sea. Following William and Ellen's marriage the couple took lodgings at 7 Smith's Arms Place, just north of the parish church of St George in the East, and Esther went to live with them. Like his father before him, William laboured in a hard, physical job on the docks. He worked as a cooper, making essential items such as a casks, barrels and hogsheads. [54] In the autumn of 1870 Esther became a grandmother as William's wife Ellen gave birth to their first born, a son whom they named William Jeremiah. Distressingly, William and Ellen were to experience the grief that Esther knew too well, as their young son died in June 1871. He was buried on 13 June 1871 in Victoria Park Cemetery, now a public recreation ground known as Meath Gardens in Bethnal Green, Tower Hamlets.

Early the following year William and Ellen had their second child, a daughter. They named her Esther Ellen. The family's fortune changed and little Esther Ellen survived. She was joined in 1874 by a sister, Catherine. Very sadly a little baby brother, also named William Jeremiah, died as an infant in 1878.

The family moved lodgings, and went to live at 6 Priory Street, Bromley by Bow, around four miles eastwards from Esther's birth street. In the spring of 1879 they were devastated by the death of Ellen, William's wife and the girls' mother. She was just thirty-four years old and had been suffering from tuberculosis. She died on 3 April 1879 at her home with her husband by her side. [55]

The family had no option but to carry on. As the year drew to a close however, Esther, now in her early seventies, was tormented. Year after year spent sewing, often by candle light in ill-lit dingy rooms, had taken its toll on her eyesight. She was afraid that she was going blind, with all that that would have meant for her future. On the morning of Tuesday 9 December 1879 her son William left for work as usual at six-thirty. He left Esther in bed asleep. At some point before nine o'clock in the morning, Esther ended her life. [56] [57] I think her choosing to die by her own hand reflects the same aspects of her personality that were shown back in 1843 as she fought to keep her family from the workhouse. She appears to have been a determined and proud woman who had simply had enough.

I haven't been able to establish where Esther was buried, but it is likely that she was interred in The City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery, known locally as Bow Cemetery. The cemetery is now managed by The Friends of Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park as a wild-flower filled nature reserve, visited by seventeen different species of bees. There was no fundraising for a sculpted monument to Esther, and outside of her family and immediate neighbourhood her death most probably passed unremarked. However, for a moment in time, her life was in the minds and on the lips of the privileged. She ignited a spark in the country's conscience.

Postscript

Esther's sister Isabella died at her daughter Emma's lodgings on 2 February 1888 at the age of eighty-two. She had continued to live on Darby Street working as a seamstress almost to the end of her life. Seven years before her death she was sharing a house with twenty-one other people. [58] Isabella was buried in Bow Cemetery on 8 February 1888.

Out of five live births only one of Esther's children survived childhood. William Jeremiah Bedell died on 29 December 1903 in the Union Workhouse in Leytonstone, East London aged sixty. [59] He had been suffering from a malignant tumour on his neck. His two daughters, Esther's grand-daughters, Esther Ellen and Catherine survived the dangers of infancy, lived to adulthood and went on to have children of their own.

"There is no death, daughter. People die only when we forget them." - Isabel Allende Eva Luna

References

- ^ Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper 21 December 1879

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1921; Reference Number: P91/LEN/A/01/Ms 7498/23

- ^ Edinburgh Evening Courant 14 July 1832

- ^ Evening Mail, London 18 August 1806

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812; Reference Number: P69/BOT2/A/008/MS09225/005

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812; Reference Number: P93/PAU3/005

- ^ The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1530

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: P71/MRY/033/001

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 4324

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: P93/PAU3/036

- ^ Kentish Gazette 3 January 1812

- ^ Grantham Journal 07 August 1886

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1931; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/038

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/012

- ^ Holmes, Isabella (1897) The London Burial Grounds

- ^ Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners for England and Wales, Volume 4 (1838) p. 139

- ^ Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser 05 December 1806

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: P69/BOT2/A/008/MS09225/005

- ^^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1921; Reference Number: P91/LEN/A/01/Ms 7498/44

- ^ London Evening Standard 19 August 1833

- ^ London Evening Standard 19 August 1834

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906/Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1906; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/017

- ^ Globe 19 July 1838

- ^ Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser 16 October 1829

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name Richard Rookwood; Registration Year 1838Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district St George in the East; Parishes for this Registration District St George in the East; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 75

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906/Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1906; Reference Number: p93/mry1/076

- ^ Name Catherine Bedell; Registration Year 1839; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 396

- ^ 1841 England Census; Class: HO107; Piece: 716; Book: 13; Civil Parish: St Mary Whitechapel; County: Middlesex; Enumeration District: 10; Folio: 51; Page: 15; Line: 5; GSU roll: 438823

- ^ Morning Post 4 June 1840

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1921; Reference Number: P91/LEN/A/01/Ms 7498/49

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Registration Year 1842; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 322

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name William Beadell; Registration Year 1843; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 420

- ^ Morning Post, London, England 11 January 1843

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915 Registration Year 1843; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 536

- ^ see Turner, Janice: An Anatomy of a 'Disorderly' Neighbourhood: Rosemary Lane and Rag Fair c.1690-1765

- ^^ Globe 26 October 1843

- ^ Jerrold, Walter, 1909, Thomas Hood: his life and times

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name Esther Bedell; Registration Year 1844; Registration Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 428

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1921; Reference Number: p93/mry2/005

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 1837-1915 Name Joseph Rookwood; Registration Year 1849; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 617

- ^ Morning Advertiser 22 December 1848

- ^ Hertford Mercury and Reformer 25 August 1849

- ^ Evening Mail 12 October 1849

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Board of Guardian Records, 1834-1906/Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1906; Reference Number: p93/geo/022

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1546; Folio: 451; Page: 7; GSU roll: 174776

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name Emma Fitsgerald; Registration Year 1851; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 2; Page 392

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1931; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/047

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name David Fitzgerald; Registration Year 1856; Registration Quarter Jul-Aug-Sep; Registration district Whitechapel; Parishes for this Registration District Whitechapel; Inferred County London; Volume 1c; Page 260

- ^^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1931; Reference Number: P93/MRY1/049

- ^ London, England, City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery Registers, 1841-1966

- ^ 1861 England Census Class: RG 9; Piece: 274; Folio: 74; Page: 40; GSU roll: 542605

- ^ 1861 England Census Class: RG 9; Piece: 274; Folio: 13; Page: 21; GSU roll: 542605

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1754-1931; Reference Number: p93/mrk/005

- ^ 1871 England Census Class: RG10; Piece: 530; Folio: 20; Page: 33; GSU roll: 823387

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name Ellen Bedell; Estimated Birth Year abt 1845; Registration Year 1879; Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun; Age at Death 34; Registration district Poplar; Parishes for this Registration District Poplar; Inferred County London; Volume 1c; Page 407

- ^ Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper 14 December 1879

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915; Name Esther Fitzgerald; Estimated Birth Year abt 1805; Registration Year 1879; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Age at Death 74; Registration district Poplar; Parishes for this Registration District Poplar; Inferred County London; Volume 1c; Page 512

- ^ 1881 England Census Class: RG11; Piece: 448; Folio: 53; Page: 1; GSU roll: 1341098

- ^ England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915 Name William Jeremiah Bedell; Estimated Birth Year abt 1848; Registration Year 1903; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Age at Death 55; Registration district West Ham; Parishes for this Registration District West Ham; Inferred County Essex; Volume 4a; Page 157